Abstract

Aims

To systematically review the outcomes and complications of cosmetic stature lengthening.

Methods

PubMed and Embase were searched on 10 November 2019 by three reviewers independently, and all relevant studies in English published up to that date were considered based on predetermined inclusion/exclusion criteria. The search was done using “cosmetic lengthening” and “stature lengthening” as key terms. The Preferred Reporting Item for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement was used to screen the articles.

Results

A total of 11 studies including 795 patients were included. The techniques used in the majority of the patients were classic 3- or 4-ring Ilizarov fixator (267 patients; 33.6%) and lengthening over nail (LON) (253 patients; 31.8%), while implantable lengthening nail (ILN) was used in the smallest number of patients (63 patients; 7.9%). Mean end lengthening achieved was 6.7 cm (SD 0.6; 1.5 to 13.0), and the mean follow-up duration was 4.9 years (SD 2.1; 41 days to 7 years). Overall, the mean number of problems, obstacles, and complications per patient was 0.78 (SD 0.5), 0.94 (SD 1.0), and 0.15 (SD 0.2), respectively. The most common problem and obstacle was ankle equinus deformity, while the most common complications were deformation of the regenerate after end of treatment and subtalar joint stiffness/deformity.

Conclusion

Cosmetic stature lengthening provides favourable height gain, patient satisfaction, and functional outcomes, with low rate of major complications. Clear indications, contraindications, and guidelines for cosmetic stature lengthening are needed.

Cite this article: Bone Joint Res 2020;9(7):341–350.

Article focus

-

Systematic review of the literature regarding cosmetic stature lengthening.

-

What are the outcomes and complications of cosmetic stature lengthening?

Key messages

-

Limb lengthening techniques can result in substantial height gain with high rate of patient satisfaction and favourable functional outcomes.

-

Shorter treatment period and lower rate of problems, obstacles, and complications were noted with the use of implantable lengthening nail (ILN) technique.

Strengths and limitations

-

This systematic review analyzed the outcomes and complications of different surgical techniques in cosmetic stature lengthening.

-

The included studies are of low level of evidence (case series or retrospective reviews).

-

The use of different limb lengthening techniques and devices on different bone segments, as well as the heterogeneity in reporting functional outcomes among the studies, make it difficult to generalize the results to one specific technique.

Introduction

Physical appearance and beauty have substantial value in our modern societies. People with short stature may, therefore, end up with considerable psychosocial disturbances, starting from adolescent age or even childhood.1,2

Limb lengthening is a commonly performed procedure for individuals with leg length discrepancy (LLD) as a result of acquired or congenital causes. When performed on both lower limbs, this procedure is referred to as stature lengthening. Stature lengthening is mainly done to improve the height of patients with dysplasia (e.g. achondroplasia).3,4 In the past few years, limb lengthening techniques have been utilized for cosmetic reasons.5-8 This is referred to as cosmetic limb lengthening or short stature lengthening. The aim of this is to improve patients’ self-esteem and ease their negative feelings regarding their short stature, in addition to improving their overall psychological and functional status.1,2,9,10

Regardless of the ethical concerns and controversies of cosmetic limb lengthening procedures, various techniques were applied for this purpose, including Ilizarov external fixation frames, lengthening over nail (LON), lengthening and then nail (LATN), and implantable lengthening nails (ILN).5-8,11-13 Multiple complications have been reported with the use of limb lengthening techniques for cosmetic indications, including pin site infections, nerve injuries, compartment syndrome, joints stiffness, and LLD.5-8,11-13 This has opened discussions among limb reconstruction experts about the indications and recommendations for cosmetic limb lengthening, but no formal consensus and guidelines have been made yet.14

In this study, we aim to systematically review the literature of cosmetic limb lengthening. We intend to assess the outcome and complications of applying the different limb lengthening techniques for cosmetic indications. We hypothesize that overall outcomes are favourable with regards to amount of height gained, and rate of substantial complications is low.

Methods

Search strategy

Three authors (YM, MA, DC) searched PubMed and Embase databases independently for relevant articles on 10 November 2019. The search was limited to English language only. The search terms “cosmetic lengthening” and “stature lengthening” were used. Although not indexed in PubMed and Embase, Journal of Limb Lengthening & Reconstruction was also searched for relevant articles since the journal is highly specialized in the topic of limb lengthening. The articles were screened based on the Preferred Reporting Item for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The following inclusion criteria were used in our systematic review: clinical studies; all level of evidence; limb lengthening done for constitutional or idiopathic short stature for cosmetic reasons; limb lengthening of the lower limbs; all lengthening techniques; and no restriction to date of publication. Studies were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: non-English articles; lengthening done for non-cosmetic indications; lengthening of the upper limbs; articles published in abstract form only; and review papers. In addition, articles about stature lengthening in general which included only few patients with cosmetic lengthening were excluded. This was because extraction of data specific to the cosmetic lengthening patients was not possible, and multiple attempts were made to contact the authors of these articles to get specific results of those patients, but the response and collaboration was extremely poor.

Data collection/extraction

The three authors (YM, MA, DC) screened the titles and abstracts of the included articles independently. To ensure completeness, articles were included in the full-text review stage if one of the three reviewers believed it should. More articles were excluded following full-text review. The three authors then independently retrieved data from the included studies in Microsoft Excel 2013 (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington, USA). The information was categorized into basic article information (e.g. title, authors, year of publication, journal, and country), patient background information and methodology details (e.g. sample size, sex, age, preoperative assessment, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and indication for surgery), surgical technique (e.g. segment lengthened and lengthening technique), and postoperative outcomes and complications (e.g. duration of follow-up, end lengthening achieved, external fixation period, external fixation index, consolidation index, rate of ILN distraction, functional/psychosocial outcomes, and complications). External fixation index is the time (days/months) spent in external fixator for every centimetre gained, while the consolidation/maturation index is time (days/months) to consolidation per centimetre of distraction gap. The rate of distraction is the total length gained divided by total number of days of distraction of an ILN. Complications were classified based on Paley’s criteria into problems, obstacles, and complications.15 The primary outcome of this review was the number of end lengthening achieved, while number of complications per patients was the secondary outcome. It is, however, not possible to set a specific cut-off number of acceptable end lengthening gained since this depends on the patients’ expectations. Meta-analysis was not done due to the heterogeneity of the included studies; however, a qualitative assessment of the data was done. Since all the included studies are of level IV evidence (all are case series studies), individual study quality assessments were not performed.

Statistical analysis

The IBM SPSS Statistics 23.0 software (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA) was used to analyze the data. This was started with descriptive analysis of all variables, including frequencies, percentages, means, SDs, and other basic statistics. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was used to test the association between polychotomous qualitative variable and normally distributed quantitative variables, while the Kruskal-Wallis test was used for quantitative variables that were not normally distributed. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered as the cut-off level of statistical significance.

Results

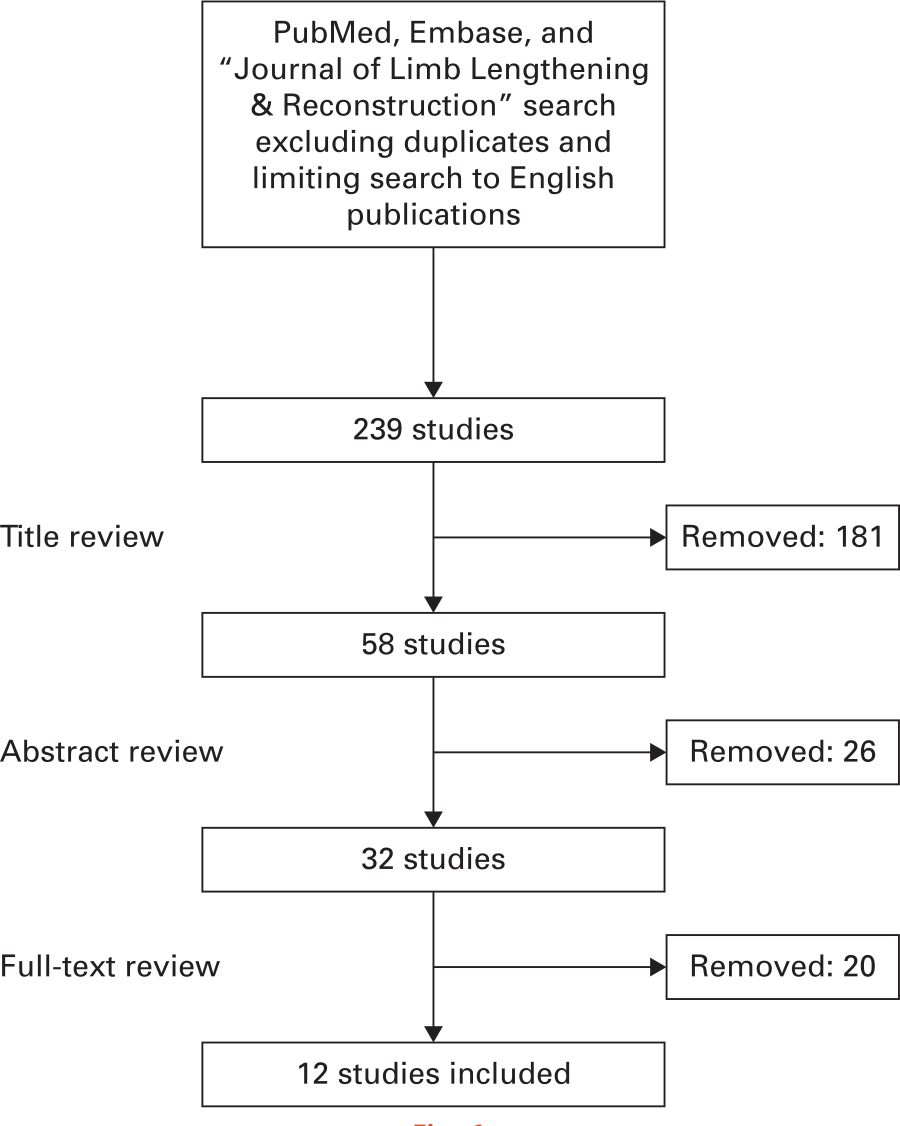

After removing the duplicates and limiting the results to English language only, the initial search yielded a total of 239 studies (Figure 1). A total of 181, 26, and 20 articles were excluded after title, abstract, and full-text review, respectively. Eventually, a total of 12 studies conducted in North America, Europe, Asia, and the Middle East were included for final analysis (Table I). One of the studies was a long-term follow-up of the same group of patients published earlier by the same senior surgeon in a previous publication, thus the data of these two studies were analyzed and presented as single study.11,16

Fig. 1

Flow diagram of the systematic search strategy.

Table I.

Background information and outcomes of patients who underwent cosmetic stature lengthening.5-8,11-13,16-21

| Study | Catagni et al 20055 | Elbatrawy and Ragab 201512 | Emara et al 2011 and 201711,16 | Guerreschi and Tsibidakis 201617 | Kocaoglu et al 20158 | Novikov et al 20146 | Novikov et al 201718 | Paley et al 20157 | Park et al 200819 | Park et al 201913 | Motallebi Zadeh et al 201420 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 54 | 50 | 32 (28 in 2017 study) | 63 | 32 | 131 | 70 | 51 | 44 | 125 | 143 |

| Sex, n | M: 32, F: 22 | M: 35, F: 15 | M: 26, F: 6 | M: 36, F: 27 | M: 24, F: 8 | M: 65, F: 66 | M: 44, F: 26 | M: 45; F: 6 | M: 24, F: 20 | N/R | M: 85, F: 58 |

| Mean age, yrs (range) | 25.8 (17.0 to 47.0) | 26.0 (17.0 to 46.0) | 27.0 (21.0 to 47.0) | 24.8 (17.0 to 48.0) | 30.0 (16.0 to 62.0) | 25.0 (14.0 to 68.0) | 27.0 (16.0 to 52.0) | 27.8 (15.0 to 51.0) | 22.7 (18.0 to 34.0) | 24.4 (16.0 to 55.0) | 26.64 (NR) |

| Mean preoperative height, cm (range) | 153 (141 to 174) | 164 (142.5 to 175) | 170 (160 to 176) | 152.6 (140 to 172) | 159 (137 to 171) | 159 (130 to 174) | 163.5 (143 to 181) | 164.7 (150 to 180) | 153.7 (140 to 163.1) | 162.1 (144 to 175) | 157.9 (N/R) |

| Technique | Hybrid advanced ring fixator | Classic 3-ring Ilizarov | LATN | Hybrid advanced ring fixator | LON | Classic 3-ring Ilizarov | Classic 3-ring Ilizarov | ILN/PRECICE* | Classic 3- or 4-ring Ilizarov (n = 16); LON (n = 28) | LATN (n = 63); LON (n = 50); ILN/ISKD (n = 12) | LON |

| Bone segment | Tibia | Tibia | Tibia | Tibia | Femur or tibia | Femur, tibia, or both | Tibia | Femur, tibia, or both | Tibia | Tibia | Tibia |

| Deformity corrected simultaneously | Varus (n = 2) | LLD (n = 1); varus (n = 6); varus and IR (n = 4) | None | Eight patients had varus | None | Varus (n = 9) | None | N/R | None | None | None |

| Mean external fixation period, days (range) | 270 (210 to 540) | 231 (166 to 369) | 96 (45 to 135) | 285 (210 to 540) | 85.9 (24 to 137) | 215 (71 to 390) | N/R | N/A | Classic: 372 (120 to 810); LON: 162 (90 to 300) | N/R | 93.7 (NR) |

| Mean external fixation index, day/cm (range)† | N/R | 34.2 (27.3 to 36.3) | 11.4 (10.8 to 12.6) | N/R | 11.2 (6.3 to 15.4) | 31 (12 to 78) | 39 (19 to 100) | N/A | Classic: 66 (24 to 180); LON: 27 (12 to 45) | N/R | 14.11 (7.43 to 28.0) |

| Mean maturation/consolidation index, day/cm (range) | N/R | N/R | 34.7 (29 to 49) | N/R | 29.96 (15 to 38.6) | 19 (5.2 to 63) | 23 (6 to 72) | N/R | Classic: 63 (30 to 171); LON: 51 (27 to 81) | N/R | N/R |

| Mean end lengthening, cm (range) | 7.0 (5.0 to 11.0) | 6.9 (4.0 to 11.0) | 7.6 (3.5 to 12.0) | 7.2 (5.0 to 11.0) | 7.5 (N/R) | 6.9 (2.0 to 13.0) | 5.9 (1.5 to 10.0) | 5.6 (1.7 to 8.0) | Overall: 6.2 (2.5 to 8.4); Classic: 5.9 (2.5 to 8.4); LON: 6.4 (3.5 to 8.0) | 6.3 (2.8 to 8.3) | 6.65 (3.5 to 13.0) |

| Mean follow-up duration (range) | 6.25 yrs (1 to 16) | 7.6 yrs (5 to 12) | 38.7 mths (24 to 93) in 2011 study. Mean of 7 yrs in 2017 study | 6.14 yrs (1 to 10) | 73 mths (12 to 163) | 5.75 yrs (1 to 14) | 4.3 yrs (2 to 8) | Until full consolidation (exact duration not reported) | Classic: 48 mths (35 to 62); LON: 40 mths (29 to 59) | 2 yrs | 14 mths (41 days to 75 mths) |

| Satisfaction and functional outcomes | Satisfactory aesthetic effect in all. Clinical outcome score they developed: 49 excellent, 5 good | Clinical outcome score developed by Catagni et alCatagni et al (2005) : 49 excellent and 1 good | 94% satisfaction rate reported in 2011 study. In 2017 study, self-esteem improved at 1 yr then returned to preoperative level at 7 yrs | All satisfied | Modified SF-3621 survey; good to excellent scores | Functional score they developed: excellent (72), good (52), satisfactory (6), poor (1). Satisfaction: all satisfied except 1 | N/R | Patients satisfied (no specific number) | Classic: 12 satisfied. LON: 22 satisfied. Overall return to activity is excellent. Around 25% in each group had difficulties in vigorous activities or strenuous sports | SARS and IKDC Subjective Form. Almost full activity. Few limitations to moderate-to-strenuous activities | Satisfaction mean score 8.7 (on a visual analogue scale consisting of 10 cm line) |

-

*

PRECICE Intramedullary Limb Lengthening System (NuVasive Specialized Orthopedics, San Diego, California, USA).

-

†

External fixation index is the time (days/months) spent in external fixator for every centimetre gained; maturation/consolidation index is time (days/months) to consolidation per centimetre of distraction gap.

-

IKDC, international knee documentation committee; ILN, implantable lengthening nail; IR, internal rotation; ISKD, intramedullary skeletal kinetic distractor; LATN, lengthening and then nail; LLD, leg length discrepancy; LON, lengthening over nail; N/A, not applicable/available; N/R, not reported; SARS, sports activity rating scale; SF-36, 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey questionnaire

The total number of patients was 795 (Table I). The male to female ratio was 1.6:1, and the mean age of the patients was 26.1 years (SD 1.9; 14 to 68). The mean preoperative height of the patients was 159.95 cm (130.00 to 181.00). The techniques used in the majority of the patients were classic 3- or 4-ring Ilizarov fixator (267 patients; 33.6%) and LON (253 patients; 31.8%), while ILN was used in the smallest number of patients (63 patients; 7.9%). Tibia was lengthened in all studies; however, three out of the 11 studies reported femur as the lengthening segment in some cases, and two out of the 11 studies lengthened both femur and tibia in some patients. A minority of patients (30 patients; 3.8%) underwent deformity correction at the same setting of limb lengthening. In cases who had external fixators, the mean external fixation period and mean external fixation index were 201.0 days (SD 99.7; 24.0 to 810.0) and 29.2 day/cm (SD 18.3; 6.3 to 180 day/cm), respectively. The mean maturation/consolidation index was 36.8 day/cm (SD 17.0; 5.2 to 171.0). Moreover, the mean end lengthening achieved was 6.7 cm (SD 0.6; 1.5 to 13.0), and the mean follow-up duration was 4.9 years (SD 2.1; 41 days to seven years). Overall, most of the patients were satisfied with the results and had excellent functional outcomes.

Tables II–IV demonstrate the problems, obstacles, and complications of cosmetic stature lengthening that were reported in the included studies. The most commonly reported problems were ankle equinus deformity and pin-track infection (Table II). Ankle equinus deformity was also the most common obstacle, where it was seen in 211 segments (Table III). On the other hand, deformation of the regenerate after end of treatment and subtalar joint stiffness/deformity were reported in 13 segments each, representing the most common complications of cosmetic stature lengthening (Table IV). Overall, the mean number of problems, obstacles, and complications per patient was 0.78 (SD 0.5), 0.94 (SD 1.0), and 0.15 (SD 0.2), respectively.

Table II.

| Study | Catagni et al 20055 | Elbatrawy and Ragab 201512 | Emara et al 2011 and 201711,16 | Guerreschi and Tsibidakis 201617 | Kocaoglu et al 20158* | Novikov et al 20146 | Novikov et al 201718 | Paley et al 20157 | Park et al 200819 | Park et al 201913 | Motallebi Zadeh et al 201420 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size, n | 54 | 50 | 32 | 63 | 32 | 131 | 70 | 51 | 44 | 125 | 143 |

| Technique | Hybrid advanced ring fixator | Classic 3-ring Ilizarov | LATN | Hybrid advanced ring fixator | LON | Classic 3-ring Ilizarov | Classic 3-ring Ilizarov | ILN/PRECICE† | Classic 3- or 4-ring Ilizarov (16); LON (28) | LATN (63); LON (50); ILN/ISKD (12) | LON |

| Total problems, n | 26 (maximum) | 60 (at least) | 16 | 42 | 23 | 22 (at least) | 16 | 8 | Classic: 19; LON: 35 | 164 | 211 (at least) |

| Number of problems per patient | < 0.48 | 1.20 (at least) | 0.50 | 0.67 | 0.72 | 0.17 (at least) | 0.23 | 0.16 | Classic: 1.19; LON: 1.25 | 1.31 | 1.47 (at least) |

| Ankle valgus, n | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Classic: 2; LON: 0 | N/A | N/A |

| Axial deviation, n | N/A | N/A | N/A | 13 | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | Classic: 2; LON: 0 | N/A | N/A |

| Behavioural problems/insomnia, n | N/A | 9 | 12 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Common peroneal nerve neuropathy, n | N/A | N/A | 3 | N/A | N/A | 5 | 4 | N/A | Classic: 2; LON: 4 | 26 | N/A |

| Deep vein thrombosis, n | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Delayed consolidation, n | N/A | N/A | 1 | N/A | N/A | 4 | 4 | 3 | N/A | 6 | N/A |

| Equinus deformity, n | N/A | N/A | N/A | 4 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Classic: 1; LON: 7 | 94 | 80 (not segments) |

| Fat embolism (suspected), n | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Fractures, n | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 |

| Hardware system error, n | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Interlocking screw breakage, n | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Classic: N/A; LON: 7 | N/A | N/A |

| Knee flexion deformity/contracture, n | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 12 | N/A | N/A | Classic: 3; LON: 4 | 10 | N/A |

| Knee subluxation, n | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Muscle contracture (not specified if knee or ankle), n | N/A | 14 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Nail breakage, n | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Pain, n | N/A | 35 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Pin tract infection, n | 26 (some needed pin removal, but number not specified) | 2 | N/A | 25 | 21 | Many (did not specify the number) | 8 | N/A | Classic: 9; LON: 13 | 28 | 84 |

| Foot rotation (ER/IR), n | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 45 |

-

*

Kocaoglu et al8 reported the number of each problem per patient (not segment).

-

†

PRECICE Intramedullary Limb Lengthening System (NuVasive Specialized Orthopedics, San Diego, California, USA).

-

ER, external rotation; ILN, implantable lengthening nail; IR, internal rotation; ISKD, intramedullary skeletal kinetic distractor; LATN, lengthening and then nail; LON, lengthening over nail; N/A, not applicable/available.

Table III.

| Study | Catagni et al 20055 | Elbatrawy and Ragab 201512 | Emara et al 2011 and 201711,16 | Guerreschi and Tsibidakis 201617 | Kocaoglu et al 20158* | Novikov et al 20146 | Novikov et al 201718 | Paley et al 20157 | Park et al 200819 | Park et al 201913 | Motallebi Zadeh et al 201420 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size, n | 54 | 50 | 32 | 63 | 32 | 131 | 70 | 51 | 44 | 125 | 143 |

| Technique | Hybrid advanced ring fixator | Classic 3-ring Ilizarov | LATN | Hybrid advanced ring fixator | LON | Classic 3-ring Ilizarov | Classic 3-ring Ilizarov | ILN/PRECICE† | Classic 3- or 4-ring Ilizarov (n = 16); LON (n = 28) | LATN (n = 63); LON (n = 50); ISKD (n = 12) | LON |

| Total obstacles, n | 23 | 72 | 47 | 54 | 2 | 28 | 47 | 12 | Classic: 60; LON: 33 | 13 | 123 |

| Number of obstacles per patient | 0.43 | 1.44 | 1.47 | 0.86 | 0.06 (at least) | 0.21 | 0.67 | 0.23 | Classic: 3.75; LON: 1.18 | 0.10 | 0.86 |

| Ankle valgus, n | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Classic: 0; LON: 2 | N/A | N/A |

| Atrophic/hypotrophic regenerate, n | N/A | 8 | N/A | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Common peroneal nerve neuropathy, n | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 | Classic: 1; LON: 0 | N/A | N/A |

| Compartment syndrome, n | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | 1 |

| Cystic regenerate, n | N/A | 4 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Deformity/axial deviation of regenerate, n | N/A | N/A | 4 | N/A | N/A | 5 | 1 | N/A | Classic: 3; LON: 0 | 2 | N/A |

| Delayed consolidation, n | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 | 3 | N/A | Classic: 5; LON: 0 | N/A | 4 |

| Distal migration of the fibula, n | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Classic: 2; LON: 2 | N/A | N/A |

| Early collapse and/or deformation after hardware removal, n | 3 | 32 | N/A | 5 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Equinus deformity, n | 19 | 24 | 32 | 42 | N/A | 10 | 34 | N/A | Classic: 7; LON: 2 | 4 | 37 |

| Hardware system error, n | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | N/A | N/A | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Haematoma, n | N/A | N/A | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Incomplete corticotomy, n | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Knee flexion deformity/contracture, n | N/A | N/A | 9 | N/A | N/A | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Knee subluxation, n | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Leg length discrepancy, n | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Locking screw backout, n | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Nail breakage, n | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 4 | N/A | N/A | 19 |

| Osteomyelitis, n | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 3 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Periprosthetic fracture, n | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Pin/wire bending/breakage, n | N/A | N/A | 1 | N/A | N/A | 5 | N/A | N/A | Classic: 38; LON: 22 | 6 | 55 |

| Pin/wire slippage, n | N/A | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 7 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Premature consolidation, n | 1 | N/A | N/A | 4 | N/A | 1 | 2 | 1 | Classic: 4; LON: 5 | N/A | 7 |

| Ring breakage, n | N/A | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

-

*

Kocaoglu et al. 2015 reported the number of each obstacle per patient (not segment).

-

†

PRECICE Intramedullary Limb Lengthening System (NuVasive Specialized Orthopedics, San Diego, California, USA).

-

ILN, implantable lengthening nail; ISKD, intramedullary skeletal kinetic distractor; LATN, lengthening and then nail; LON, lengthening over nail; N/A, not applicable/available.

Table IV.

| Study | Catagni et al 20055 | Elbatrawy and Ragab 201512 | Emara et al 2011 and 201711,16 | Guerreschi and Tsibidakis 201617 | Kocaoglu et al 20158* | Novikov et al 20146 | Novikov et al 201718 | Paley et al 20157 | Park et al 200819 | Park et al 201913 | Motallebi Zadeh et al 201420 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size, n | 54 | 50 | 32 | 63 | 32 | 131 | 70 | 51 | 44 | 125 | 143 |

| Technique | Hybrid advanced ring fixator | Classic 3-ring Ilizarov | LATN | Hybrid advanced ring fixator | LON | Classic 3-ring Ilizarov | Classic 3-ring Ilizarov | ILN/PRECICE† | Classic 3- or 4-ring Ilizarov (n = 16); LON (n = 28) | LATN (n = 63); LON (n = 50); ISKD (n = 12) | LON |

| Total complications, n | 22 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 10 | 11 | 13 | 1 | Classic: 8; LON: 1 | 0 | 4 |

| Number of complications per patient, n | 0.41 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.31 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 0.02 | Classic: 0.50; LON: 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| Common peroneal nerve palsy, n | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Deformation of regenerate after end of treatment, n | N/A | N/A | 1 | N/A | N/A | 4 | 7 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Delayed consolidation, n | 2 | N/A | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Classic: 5; LON: 0 | N/A | 1 |

| Fascia lata/iliotibial band contracture, n | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Fracture through the regenerate, n | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Foot drop requiring tendon transfer, n | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Hardware (e.g. screws) irritation required removal, n | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 7 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Impaired ankle dorsiflexion ( < 20°), n | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 4 | 1 | N/A | Classic: 2; LON: 1 | N/A | N/A |

| Incomplete consolidation of the regenerate, n | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Intraoperative fractures, n | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 3 |

| Knee subluxation, n | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Leg length discrepancy, n | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Residual axial deviation, n | 10 | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Residual knee flexion deformity/loss of knee extension, n | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Scar revision, n | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Subtalar joint stiffness/deformity, n | 5 | N/A | N/A | 6 | N/A | N/A | 1 | N/A | Classic: 1; LON: 0 | N/A | N/A |

-

*

Kocaoglu et al. 2015 reported the number of each complication per patient (not segment).

-

†

PRECICE Intramedullary Limb Lengthening System (NuVasive Specialized Orthopedics, San Diego, California, USA).

-

ILN, implantable lengthening nail; ISKD, intramedullary skeletal kinetic distractor; LATN, lengthening and then nail; LON, lengthening over nail; N/A, not applicable/available.

Table V summarizes the outcomes and complications based on the lengthening technique used. The highest mean end lengthening achieved was seen with LATN technique (7.6 cm (3.5 to 12.0)), while the lowest was with ILN (5.6 cm (1.7 to 8.0)). Mean external fixation index was the lowest among the LATN group (11.4 day/cm (10.8 to 12.6)), while the highest was among the classic Ilizarov frame group (42.5 day/cm (SD 16.0)). In addition, lowest numbers of problems, obstacles, and complications per patient were all seen in the ILN group. None of these differences, however, were statistically significant.

Table V.

Association between cosmetic lengthening technique and outcomes and complications.

| Outcomes/complications | Lengthening technique | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classic Ilizarov frame | Hybrid advanced ring fixator | Lengthening over nail | Lengthening and then nail | Implantable lengthening nail | ||

| Mean end lengthening, cm (SD) | 6.4 (0.6) | 7.1 (0.1) | 6.8 (0.6) | 7.6* | 5.6* | 0.155† |

| Mean external fixation index, day/cm (SD) | 42.5 (16.0) | N/A | 17.4 (8.4) | 11.4* | N/A | 0.092† |

| Mean number of problems per patient (SD) | 0.7 (0.6) | 0.6 (0.1) | 1.1 (0.4) | 0.5* | 0.16* | 0.439† |

| Mean number of obstacles per patient (SD) | 1.5 (1.6) | 0.6 (0.3) | 0.7 (0.6) | 1.5* | 0.23* | 0.595‡ |

| Mean number of complications per patient (SD) | 0.2 (0.2) | 0.2 (0.2) | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.6* | 0.02* | 0.361‡ |

-

*

SD not available.

-

†

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) test.

-

‡

Kruskal-Wallis test.

-

N/A, not applicable/available.

Discussion

This systematic review of 795 patients reveals that limb lengthening techniques can result in substantial height gain with high rate of excellent patient satisfaction and functional outcomes, although some authors did not use validated instruments to assess outcomes. Shorter treatment period and lower rate of problems, obstacles, and complications were seen with the use of ILN technique. Overall, the rate of serious major complications was low for cosmetic limb lengthening; however, the treating surgeon should be experienced in managing minor problems and obstacles to avoid increasing the rate of serious complications and their consequences.

Short stature, although not considered as an illness when no underlying cause is present, might result in psychological and functional limitations to the individual.1,2,22-25 It can negatively impact many aspects of a person’s life, including career opportunity and success, interpersonal attraction, and mate selection.26-29 The majority of patients who seek cosmetic stature lengthening report a family concern or peer appraisal about their height in childhood.7 Being sensitized to height issues early in life have shown to affect a person’s life during adulthood.24 For males, short stature is more concerning, more stigmatizing, and less culturally accepted compared to females.23,26,28,29 As a result, more men than women seek stature lengthening as noted in this systematic review.

Cosmetic stature lengthening resulted in improved self-esteem and quality of life, and decreased distress and shyness levels.5-7,11,12,16-19 Most patients reported high satisfaction rate and felt they would recommend the surgery for others with short stature.5,6,17 Satisfaction, however, might not be predictable in patients with body dysmorphic disorder or dysmorphophobia.30 These patients experience a distressing and impairing preoccupation of an imagined appearance, and hence seek cosmetic surgery to alter their subjective perceived abnormal appearance. Preoperative psychological evaluation is, therefore, mandatory in patients seeking cosmetic limb lengthening to rule out psychiatric disorders and understand the patient’s personality and motivations. In addition to the psychological assessment, extensive preoperative counselling with the treating surgeon is a must. This should be done with an aim to determine whether the patient needs the surgery or not, to make him/her aware of the nature of the treatment and its possible complications, and to discuss and suggest other non-surgical options whenever possible.

Many patients who are counselled for cosmetic limb lengthening might not be good surgical candidates because they show features of dysmorphophobia, have unrealistic expectations of treatment outcomes, or show poor motivation in collaborating with long-term postoperative protocols. Some of those who are being rejected for surgery might go to centres or surgeons with minimal or no experience in limb lengthening techniques and end up with serious complications as noted by some authors.6 With the lack of clear indications and contraindications on when to offer this surgery to individuals with short stature, and the ethical controversies behind it, guidelines for cosmetic limb lengthening are needed.14 Guidelines should clearly explain at least: 1) indications and contraindications of the surgery; 2) preferred and acceptable lengthening technique; 3) level of training and experience of the surgeon needed to perform the surgery; 4) quality and setup of the facility where the surgery is being done; 5) preoperative counselling and psychological assessments needed; 6) definitions of acceptable outcomes; 7) protocols on how to manage common related complications; and 8) postoperative follow-up protocols.

Several limitations exist in the current study. The included studies have a low level of evidence (case series or retrospective reviews). Moreover, different limb lengthening techniques and devices have been used on different bone segments, making it difficult to generalize the results to one specific technique. Reporting outcomes varied in between the included studies as well, with some studies missing important outcomes like maturation/consolidation index, and other studies using unvalidated outcome scores. This makes it difficult to compare functional outcomes in between the lengthening techniques used. Factors associated with poor satisfaction rate and outcomes were also not well-reported. Understanding the predictors of good outcomes would help the surgeons to select patients for cosmetic stature lengthening. The association between patients’ preoperative expectations in length gain, careful understanding of the possible complications that might occur with greater limb lengthening, and patient satisfaction of the outcome of this surgery needs to be studied in depth.

In conclusion, cosmetic stature lengthening provides favourable height gain, patient satisfaction, and functional outcomes, with a low rate of major complications. However, clear indications, contraindications, and guidelines for cosmetic stature lengthening are required.

References

1. Stathis SL , O’Callaghan MJ , Williams GM , et al. Behavioural and cognitive associations of short stature at 5 years . J Paediatr Child Health . 1999 ; 35 ( 6 ): 562 – 567 . Crossref PubMed Google Scholar

2. Kranzler JH , Rosenbloom AL , Proctor B , Diamond FB , Watson M . Is short stature a handicap? A comparison of the psychosocial functioning of referred and nonreferred children with normal short stature and children with normal stature . J Pediatr . 2000 ; 136 ( 1 ): 96 – 102 . Crossref PubMed Google Scholar

3. Cattaneo R , Villa A , Catagni M , Tentori L . Limb lengthening in achondroplasia by Ilizarov’s method . Int Orthop . 1988 ; 12 ( 3 ): 173 – 179 . Google Scholar

4. Correll J , Held P . [Limb lengthening in dwarfism] . Orthopade . 2000 ; 29 ( 9 ): 787 – 794 . Crossref PubMed Google Scholar

5. Catagni MA , Lovisetti L , Guerreschi F , Combi A , Ottaviani G . Cosmetic bilateral leg lengthening: experience of 54 cases . J Bone Joint Surg Br . 2005 ; 87-B ( 10 ): 1402 – 1405 . Crossref PubMed Google Scholar

6. Novikov KI , Subramanyam KN , Muradisinov SO , Novikova OS , Kolesnikova ES . Cosmetic lower limb lengthening by Ilizarov apparatus: what are the risks? Clin Orthop Relat Res . 2014 ; 472 ( 11 ): 3549 – 3556 . Crossref PubMed Google Scholar

7. Paley D , Debiparshad K , Balci H , Windisch W , Lichtblau C . Stature lengthening using the PRECICE intramedullary lengthening nail . Techniques in Orthopaedics . 2015 ; 30 ( 3 ): 167 – 182 . Google Scholar

8. Kocaoglu M , Bilen FE , Eralp IL , Yumrukcal F . Results of cosmetic lower limb lengthening by the lengthening over nail technique . Acta Orthop Belg . 2017 ; 83 ( 2 ): 231 – 244 . PubMed Google Scholar

9. Stratford R , Mulligan J , Downie B , Voss L . Threats to validity in the longitudinal study of psychological effects: the case of short stature . Child Care Health Dev . 1999 ; 25 ( 6 ): 401 – 409 . Crossref PubMed Google Scholar

10. Scott PA , Candler PD , Li JC . Stature and seat position as factors affecting fractionated response time in motor vehicle drivers . Appl Ergon . 1996 ; 27 ( 6 ): 411 – 416 . Crossref PubMed Google Scholar

11. Emara K , Farouk A , Diab R . Ilizarov technique of lengthening and then nailing for height increase . J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) . 2011 ; 19 ( 2 ): 204 – 208 . Crossref PubMed Google Scholar

12. Elbatrawy Y , Ragab IM . Safe Cosmetic Leg Lengthening for Short Stature: long-term Outcomes . Orthopedics . 2015 ; 38 ( 7 ): e552 – e560 . Crossref PubMed Google Scholar

13. Park KB , Kwak YH , Lee JW , et al. Functional recovery of daily living and sports activities after cosmetic bilateral tibia lengthening . Int Orthop . 2019 ; 43 ( 9 ): 2017 – 2023 . Crossref PubMed Google Scholar

14. Patel M . Cosmetic limb lengthening surgery: the elephant in the room. harm minimization not prohibition . J Limb Lengthen Reconstr . 2017 ; 3 ( 2 ): 73 – 74 . Google Scholar

15. Paley D , Problems PD . Problems, obstacles, and complications of limb lengthening by the Ilizarov technique . Clin Orthop Relat Res . 1990 ; 250 : 81 – 104 . PubMed Google Scholar

16. Emara K , Al Kersh MA , Emara AK . Long term self Esteem assessment after height increase by lengthening and then nailing . Acta Orthop Belg . 2017 ; 83 ( 1 ): 40 – 44 . PubMed Google Scholar

17. Guerreschi F , Tsibidakis H . Cosmetic lengthening: what are the limits? J Child Orthop . 2016 ; 10 ( 6 ): 597 – 604 . Crossref PubMed Google Scholar

18. Novikov KI , Subramanyam KN , Kolesnikova ES , Novikova OS , Jaipuria J . Guidelines for safe bilateral tibial lengthening for stature . J Limb Lengthening Reconstr . 2017 ; 3 : 93 – 100 . Google Scholar

19. Park HW , Yang KH , Lee KS , et al. Tibial lengthening over an intramedullary nail with use of the Ilizarov external fixator for idiopathic short stature . J Bone Joint Surg Am . 2008 ; 90-A ( 9 ): 1970 – 1978 . Crossref PubMed Google Scholar

20. Motallebi Zadeh N , Mortazavi SH , Khaki S , et al. Bilateral tibial lengthening over the nail: our experience of 143 cases . Arch Orthop Trauma Surg . 2014 ; 134 ( 9 ): 1219 – 1225 . Crossref PubMed Google Scholar

21. Ware JE , Sherbourne CD . The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. conceptual framework and item selection . Med Care . 1992 ; 30 ( 6 ): 473 – 483 . PubMed Google Scholar

22. Skuse D . The psychological consequences of being small . J Child Psychol Psychiatry . 1987 ; 28 ( 5 ): 641 – 650 . Crossref PubMed Google Scholar

23. Booth ND . The relationship between height and self-esteem and the mediating effect of Self-Consciousness . J Soc Psychol . 1990 ; 130 ( 5 ): 609 – 617 . Google Scholar

24. Busschbach JJ , Rikken B , Grobbee DE , De Charro FT , Wit JM . Quality of life in short adults . Horm Res . 1998 ; 49 ( 1 ): 32 – 38 . Google Scholar

25. Steinhausen HC , Dörr HG , Kannenberg R , Malin Z . The behavior profile of children and adolescents with short stature . J Dev Behav Pediatr . 2000 ; 21 ( 6 ): 423 – 428 . Crossref PubMed Google Scholar

26. Pawlowski B , Dunbar RI , Lipowicz A . Tall men have more reproductive success . Nature . 2000 ; 403 ( 6766 ): 156 . Crossref PubMed Google Scholar

27. Judge TA , Cable DM . The effect of physical height on workplace success and income: preliminary test of a theoretical model . J Appl Psychol . 2004 ; 89 ( 3 ): 428 – 441 . Crossref PubMed Google Scholar

28. Hensley WE . Height as a basis for interpersonal attraction . Adolescence . 1994 ; 29 ( 114 ): 469 – 474 . PubMed Google Scholar

29. Gillis JS , Avis WE . The Male-Taller norm in mate selection . Pers Soc Psychol Bull . 1980 ; 6 ( 3 ): 396 – 401 . Google Scholar

30. Fang A , Matheny NL , Wilhelm S . Body dysmorphic disorder . Psychiatr Clin North Am . 2014 ; 37 ( 3 ): 287 – 300 . Crossref PubMed Google Scholar

Author contributions

Y. Marwan: Performed the literature search, Extracted the data, Analyzed the statistics.

D. Cohen: Performed the literature search, Extracted the data.

M. Alotaibi: Performed the literature search, Extracted the data.

A. Addar: Analyzed the statistics.

M. Bernstein: Supervised the research.

R. Hamdy: Supervised the research.

Funding statement

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

ICMJE COI statement

None declared.

Acknowledgements

None declared.

Ethical review statement

This study did not require ethical approval.

© 2020 Author(s) et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) licence, which permits the copying and redistribution of the work only, and provided the original author and source are credited. See https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.