Abstract

Objectives

Temperature is known to influence muscle physiology, with the velocity of shortening, relaxation and propagation all increasing with temperature. Scant data are available, however, regarding thermal influences on energy required to induce muscle damage.

Methods

Gastrocnemius and soleus muscles were harvested from 36 male rat limbs and exposed to increasing impact energy in a mechanical test rig. Muscle temperature was varied in 5°C increments, from 17°C to 42°C (to encompass the in vivo range). The energy causing non-recoverable deformation was recorded for each temperature. A measure of tissue elasticity was determined via accelerometer data, smoothed by low-pass fifth order Butterworth filter (10 kHz). Data were analysed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and significance was accepted at p = 0.05.

Results

The energy required to induce muscle failure was significantly lower at muscle temperatures of 17°C to 32°C compared with muscle at core temperature, i.e., 37°C (p < 0.01). During low-energy impacts there were no differences in muscle elasticity between cold and warm muscles (p = 0.18). Differences in elasticity were, however, seen at higher impact energies (p < 0.02).

Conclusion

Our findings are of particular clinical relevance, as when muscle temperature drops below 32°C, less energy is required to cause muscle tears. Muscle temperatures of 32°C are reported in ambient conditions, suggesting that it would be beneficial, particularly in colder environments, to ensure that peripheral muscle temperature is raised close to core levels prior to high-velocity exercise. Thus, this work stresses the importance of not only ensuring that the muscle groups are well stretched, but also that all muscle groups are warmed to core temperature in pre-exercise routines.

Cite this article: Professor A. H. R. W. Simpson. Increased risk of muscle tears below physiological temperature ranges. Bone Joint Res 2016;5:61–65. doi: 10.1302/2046-3758.52.2000484.

Article focus

-

Temperature is known to influence muscle contractile properties, however, there are limited data as to whether temperature influences the energy required to induce muscle damage.

-

The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of temperature on the energy required to achieve a permanent deformation of muscle tissue.

Key messages

-

The energy required to induce muscle failure is influenced by muscle temperature. When muscle temperature drops below core body temperature (37°C), less energy is required to cause a muscle tear.

-

There is a similar elastic response between cold and warm tissue when the energy input to the muscle is low, however, as the energy input increases, colder tissue displays a stiffer response and is more prone to damage.

-

Muscle temperatures of 32°C are reported in ambient conditions, suggesting that it may be prudent to ensure that peripheral muscle temperature is raised close to core levels prior to high velocity exercise.

Strengths and limitations

-

The experimental design allowed for an instantaneously applied high rate of strain along the lines of muscle force, hence mimicking the situation where muscle tears occur.

-

The primary limitation is that we assessed strain of passive muscle using forced stretching of harvested tissue. The benefit of this approach is that it allows tight control of the test environment. However, it is possible that the (untested) active component of force generation may also influence the failure energy.

Introduction

Skeletal muscle is regularly exposed to potentially injurious forces. In sports, it is often suggested that up to 50% of all injuries are related to muscle,1,2 mostly due to mechanical trauma,3 presenting a clinical challenge to primary care and sports medicine. Muscle strain typically occurs through excessive tensile loads resulting in an ‘overstretching’ of the muscle.3 With public health initiatives to increase the activity level of the population (particularly the most sedentary), there is a danger that rates of disabling muscle tears may increase drastically.

‘Warm-ups’ are recommended prior to exercise as they are considered to reduce the risk of injury and increase performance.4,5 However, the nature of the warm-up varies widely and often concentrates on stretching rather than increasing the temperature of the muscle. The warming component of the warm-up is recommended to be one that produces a mild sweat without fatiguing the individual.6 Current warm-ups are not aimed specifically at increasing the temperature of peripheral muscles. Yet, the muscle temperature can vary widely and is dependent on its location, the activity level and the ambient environmental conditions. As a result, large temperature gradients can exist with muscles. Although core body temperature is kept relatively constant, this is often at the expense of the peripheral tissues.7 In moderate environmental conditions, the deep musculature maintains core body temperature, however, superficial muscles, such as the hamstrings and rotator cuff muscles, can have temperatures in the low 30s, and remarkably, even in the mid 20s, in cold environments.8

The effect of muscle temperature on muscle tears is poorly studied, and only scant experimental data are available regarding thermal influences on the energy required to induce muscle strain. Noonan et al8 investigated the influence of temperature on muscles when they were stretched gradually at either 25°C or 40°C and found that the mean stiffness was higher in cold muscles, implying that warming may be protective of injury. As indicated above, peripheral muscle temperatures are often below core temperature, yet the effect of different temperatures across this in vivo range on the risk of injury when muscles are subjected to explosive, potentially tearing forces, is unknown.

The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of temperature on the energy required to achieve a permanent deformation of the muscle tissue, i.e., a tear. The secondary aim was to evaluate the influence of temperature on muscle elastic properties.

Materials and Methods

In total, 18 pairs of hind limbs were obtained from the cadavers of ex-breeder Sprague-Dawley rats with a mean weight of 421 (sd 40) grams. Within ten minutes of death the limbs were skinned, and gastrocnemius and soleus exposed. The remaining musculature of the thigh and lower limb were removed, and tibia and fibula cut. Each gastrocnemius/soleus muscle group was heated to one of six specific temperatures (ranging from 17°C to 42°C, in 5°C increments) in a saline bath. The length of the muscle was measured before clamping the femoral condyles and foot of the rat. A thermocouple (RS IEC Electrocomponents plc, Oxford, United Kingdom) was embedded in the muscle to maintain constant measurement of temperature.

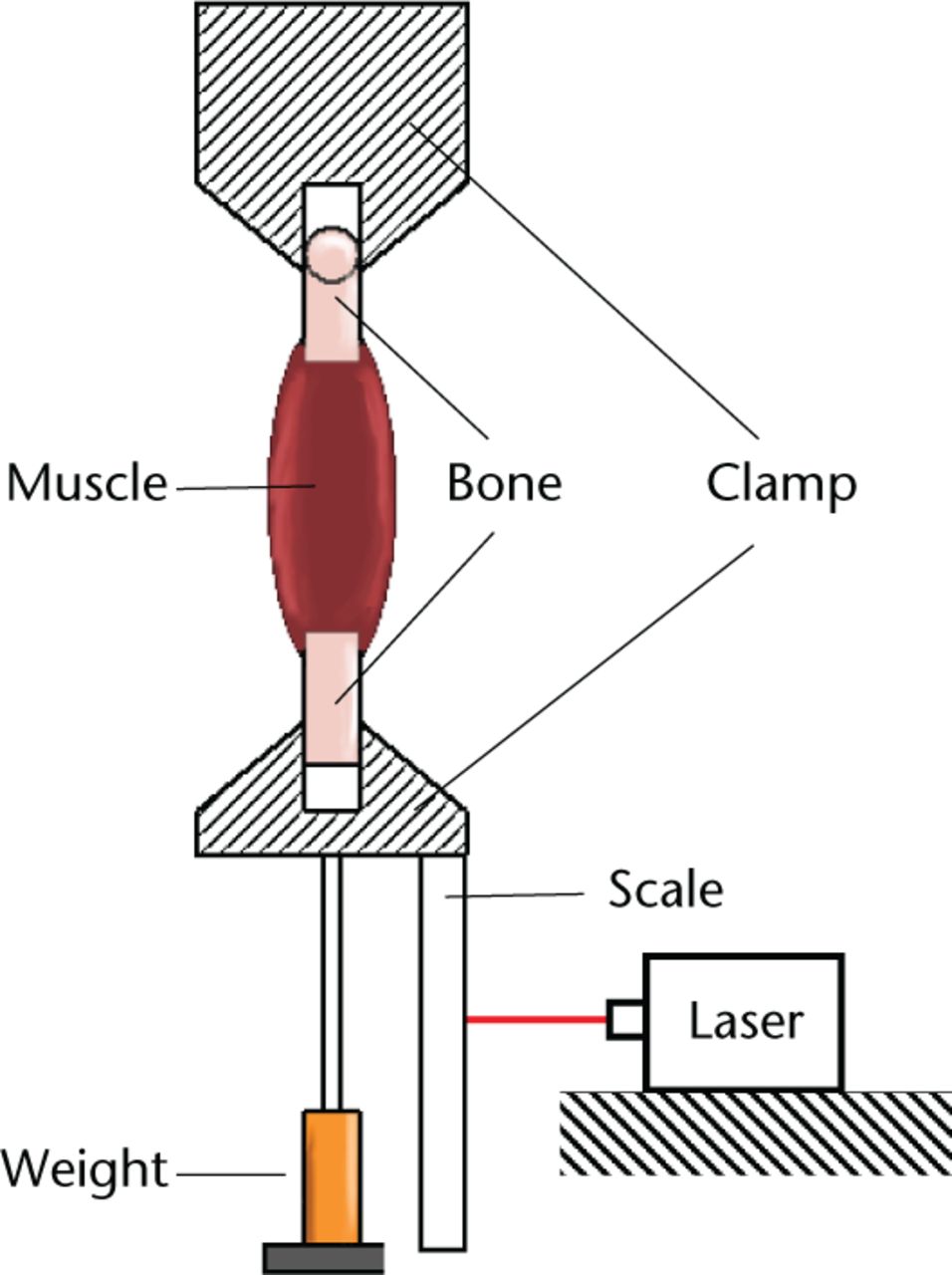

The muscle attachments (femur and foot) were clamped, taking care to ensure that the muscle was not trapped. The clamps and muscle were surrounded by a plastic insulating envelope which prevented drying. Two 20W halogen lamps focused on the envelope were used to keep the temperature constant. Resting lengths of the muscles were measured under test conditions (preload of clamp = 186.5 g) using a cross generating red laser (λ = 635 nm, Global MaxiBrite Miniature Series, Class 2 (Global Laser Ltd, Gwent, United Kingdom)) mounted on the frame. A rule attached to the lower clamp enabled measurements to be taken within 1 mm (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1

Diagram showing the experiemental setup.

A known mass (97.1 g) was dropped from 20 mm, causing an impact load on the muscle. The drop height was increased in steps of 10 mm until failure was observed. An accelerometer (PCB 353B18 (PCB Piezotronics Inc., Depew, New York) was attached to the lower clamp, and digitally recorded on a picoscope (Pico Technology, Cambridgeshire, United Kingdom) data acquisition system. In total, six limbs (three rats) were used for each of the six temperatures. The initial length and length after one minute were recorded, so that the muscle had adequate time to recover after impact loading. A 1 mm difference in muscle length indicated that the muscle had lengthened and sustained a non-recoverable deformation such as a muscle tear. The drop height at which this occurred determined the failure energy.

The output from the accelerometer was fed into a custom MatLab (Mathworks, Natick, Massachusetts) script where the data were smoothed by passing through a low-pass fifth order Butterworth filter (10 kHz). The maximum and minimum values were identified and the difference in time between these two extremes was extracted. This time value was representative of the time it took for the muscle to undergo maximum acceleration and rebound which we have defined as elasticity, and can be taken as a representative measure of the stiffness of the muscle tissue before failure.

Histological specimens were obtained from limbs immediately following test to failure. These samples were fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin. Serial sections were cut and stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E). These sections confirmed that there was disruption of the connective tissue component of the muscle.

Specific IRB approval was not required for this article as cadaveric animal tissue was used; this was done under the appropriate United Kingdom licence at an approved laboratory, and according to local animal welfare policy.

Statistical analysis

Data are reported with means and standard deviations (sd) as a measure of dispersion. Differences in failure energy were evaluated by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post hoc pairwise comparison (Tukey HSD test). Data were assessed in SPSS version 19 (IBM, Armonk, New York) and MatLab (Mathworks, Natick, Massachusetts).

Results

The number of test limbs, animal mass, and pre-test muscle length were similar between temperature groups (p = 0.2, Table I).

Table I.

Test group baseline characteristics (mean, (standard deviation)).

| Temperature (°) | 17 | 22 | 27 | 32 | 37 | 42 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| rat weight (g) | 440.7 (54.5) | 395.3 (9.3) | 430.3 (16.3) | 426.7 (15.4) | 452.3 (47.4) | 382.3 (48.6) |

| muscle length (mm) | 47.5 (1.0) | 46.7 (0.5) | 47.2 (0.8) | 46.2 (0.8) | 46.7 (0.5) | 46.5 (0.5) |

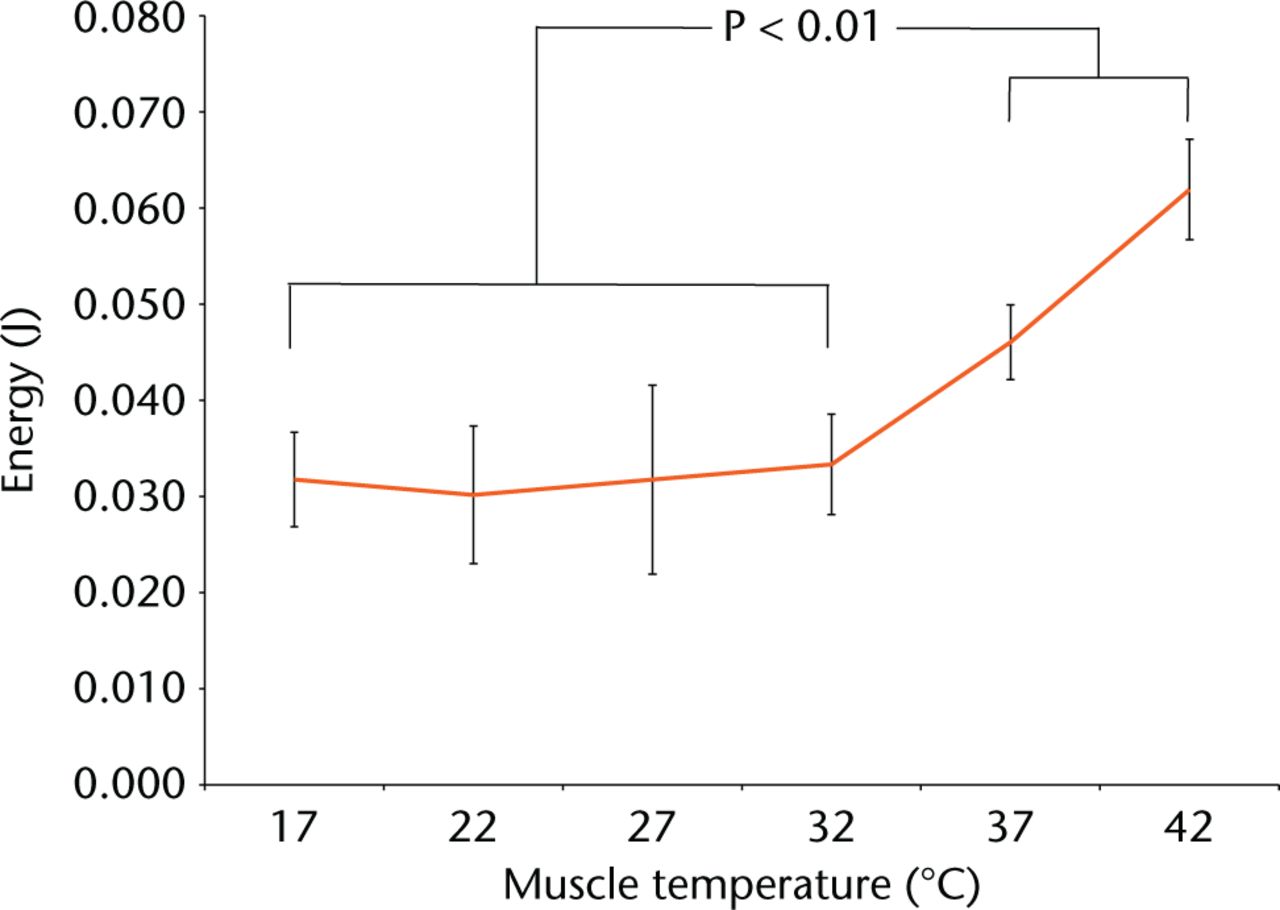

Energy at muscle failure differed with temperature (Fig. 2). The energy at failure was significantly lower at 32°C and below (Fig. 2, one way ANOVA, p < 0.01). Post hoc Tukey pairwise comparisons highlighted that temperatures of 37°C and 42°C differed from the other temperatures, but not from each other.

Fig. 2

Graphs showing energy to cause permanent post-loading deformation.

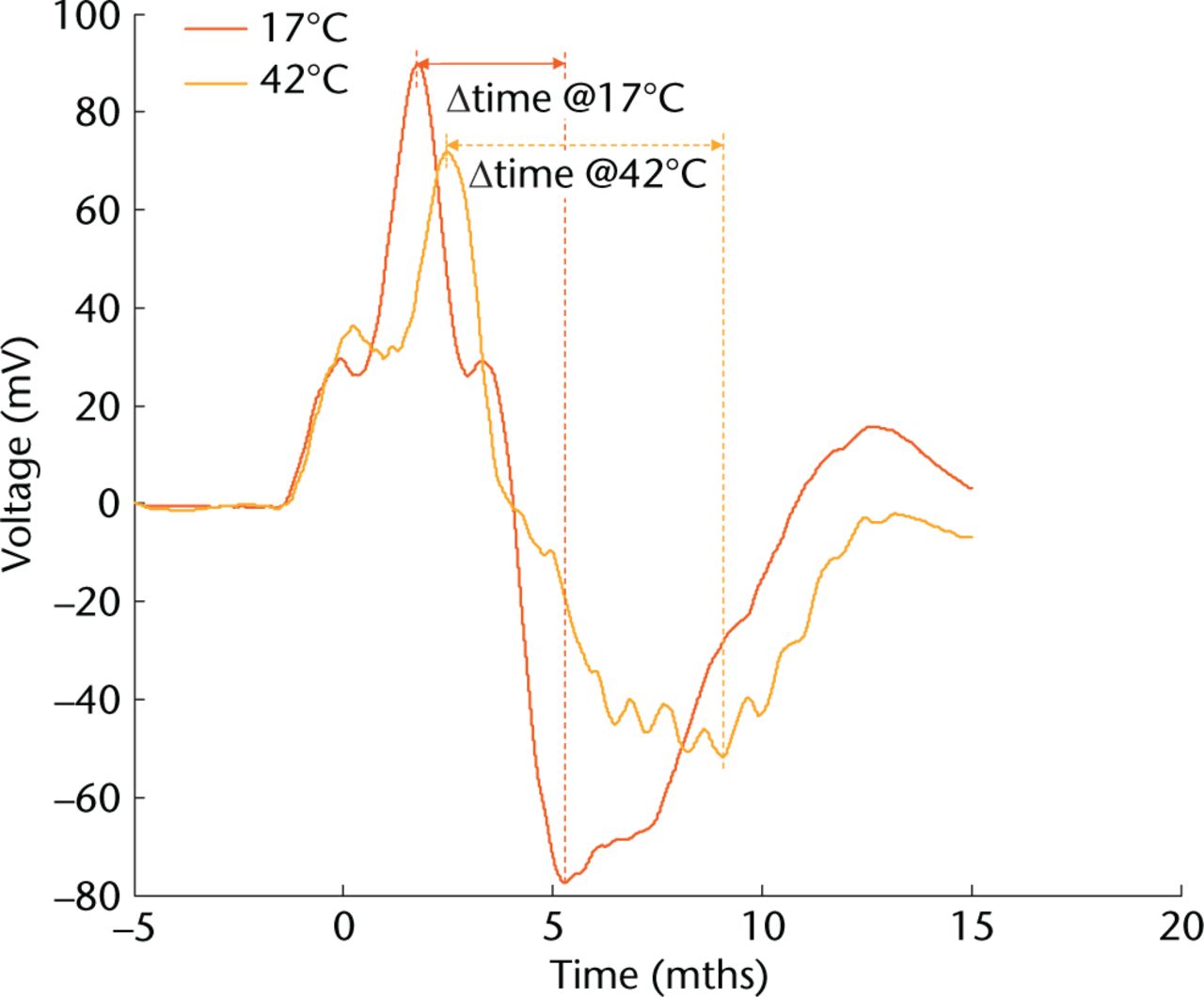

As energy to failure highlighted an apparent dichotomy above and below 32°C, 17°C to 32°C were grouped as ‘cold’ and 37°C to 42°C grouped as ‘warm’ for further analysis. Elasticity was defined as a function of the acceleration and rebound time (Fig. 3). When investigating a 20 mm drop height, there was no difference in muscle elasticity between cold and warm temperatures (p = 0.18). Differences in elasticity were, however, seen at drop heights of 30 mm (p = 0.02) and at 40 mm (p = 0.01) (Table II).

Fig. 3

Graph showing the effect of muscle temperature on duration of elongation. Example accelerometer graphs from dynamic testing of muscle tissue at cold (17°C) and warm (42°C) temperatures. Acceleration is derived from the voltage output. The time taken from maximum to minimum acceleration values was used as an indication of muscle stiffness.

Table II.

Muscle rebound duration by drop height (mean, standard deviation).

| Height | Group | Rebound duration (ms) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20 mm | cold | 4.79 (1.19) | 0.18 |

| warm | 5.71 (1.86) | ||

| 30 mm | cold | 4.17 (1.54) | 0.02 |

| warm | 5.55 (1.29) | ||

| 40 mm | cold | 3.57 (0.78) | 0.01 |

| warm | 5.71 (2.26) |

Discussion

Previous studies have examined the effect of temperature on the active component of the muscle.8-11 In these, temperature was found to influence muscle function. specifically to affect maximal force and endurance time9,10 as well as the velocity of shortening8 and the amplitude of muscle action potentials.11 The current study has focused on the passive properties of the muscle.

The aim of this study was to determine the effect of temperature on the energy required to achieve a permanent deformation of muscle tissue such as a tear. We found that when muscle temperature drops below core body temperature (37°C), less energy was required to cause a muscle tear. Importantly, there was no difference in the energy required to cause non-recoverable muscle tissue deformation between the temperature ranges of 17°C and 32°C, suggesting that even modest reductions in peripheral muscle temperature may be associated with tears.

Previously, it has been suggested that an increased temperature may reduce the elastic modulus.12 Our results concur with this as we found that when the energy input to the muscle was ‘low’ there was a similar elastic response between cold and warm tissue. However, as this energy input increased, colder tissue displayed a significantly stiffer response and was more prone to damage. We defined cold muscle as that below 32°C. This is of particular clinical relevance, as this muscle temperature is reported in ambient conditions.8 These findings perhaps highlight the importance of a graded warm-up regimen (incorporating low energy exercise) aimed at raising peripheral muscle temperatures to over 32°C prior to structured exercise, particularly in cold environmental temperatures. However, in an experimental model, Saffran et al4 found that preconditioning of the muscle only produced an increase in temperature of 1°C. This modest effect on the muscle temperature may in part explain the lack of clarity in the current evidence base regarding the effectiveness of pre-exercise warm-up.13,14 Indeed, no ‘reduction in risk’ of injury was reported from trials examining pre-exercise and post half-time warm-ups.15,16 Thus, although current warm-ups may have a beneficial effect on improving performance,14 there is no evidence that the warm-ups as they are currently performed reduce the risk of injury.

These findings, along with our results, suggest that in colder climates muscle activity alone may not be sufficient to maintain the muscle temperature at a level that minimises the risk of injury, i.e., over 32°C. Thus in cold, wet or windy conditions which will reduce the muscle temperature, clothing specifically designed to maintain the temperature of peripheral muscles closer to core temperature may be of great benefit in reducing the number of muscle tears.

The experimental design allowed an instantaneously applied high rate of strain along the lines of muscle force which mimics the situation where muscle tears occur. The primary limitation of this work, however, is that we assessed strain of passive muscle using forced stretching of harvested tissue. The benefit of this approach was that it allowed tight control of the test environment, however, it is possible that the additional active component of force generation may influence the failure energy. While we acknowledge that our experimental design does not directly replicate the clinical situation, we believe the findings are clinically relevant as the connective tissue component is likely to behave in a similar manner both ex vivo and in vivo.

Muscle strains result in significant morbidity. The healthcare burden and economic impact of these injuries may increase in tandem with public health initiatives to increase activity and sports participation. As such, it is important that preventative strategies are employed to mitigate the risk of injury. Our findings indicate that when peripheral muscle temperature drops, less energy is required to cause muscle tears. Some could be prevented, particularly in colder environments, by ensuring that peripheral muscle temperature is raised close to core levels prior to high velocity exercise.

Funding Statement:

None declared.

ICMJE conflict of interest:

Dr Hamilton reports funding received from Stryker and ARUK, none of which is related to this article.

Professor Simpson reports funding received from Stryker, RCSEd, OTCF, ARUK, ORUK, and EPSRC, none of which is related to this article.

References

1 Järvinen TAH , JärvinenTLN, KääriäinenM, KalimoH, JärvinenM. Biology of muscle trauma. Am J Sports Med2005;33:745-766. Google Scholar

2 Garrett WE Jr . Muscle strain injuries. Am J Sports Med1996;24(6 Suppl):S2-S8.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

3 Järvinen TA , JärvinenTL, KääriäinenM, et al.. Muscle injuries: optimising recovery. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol2007;21:317-331.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

4 Safran MR , GarrettWEJr, SeaberAV, GlissonRR, RibbeckBM. The role of warmup in muscular injury prevention. Am J Sports Med1988;16:123-129.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

5 Faulkner SH , FergusonRA, GerrettN, et al.. Reducing muscle temperature drop after warm-up improves sprint cycling performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc2013;45:359-365.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

6 Woods K , BishopP, JonesE. Warm-up and stretching in the prevention of muscular injury. Sports Med2007;37:1089-1099.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

7 Holewijn M , HeusR. Effects of temperature on electromyogram and muscle function. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol1992;65:541-545.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

8 Noonan TJ , BestTM, SeaberAV, GarrettWEJr. Thermal effects on skeletal muscle tensile behavior. Am J Sports Med1993;21:517-522.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

9 Bennett AF . Thermal dependence of muscle function. Am J Physiol1984;247(2 Pt 2):R217-R229.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

10 Brooks GAK , HittelmanKJ, FaulknerJA, BeyerRE. Temperature, skeletal muscle mitochondrial functions, and oxygen debt. Am J Physiol1971;220:1053-1059.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

11 Ricker K , HertelG, StodieckG. Increased voltage of the muscle action potential of normal subjects after local cooling. J Neurol1977;216:33-38.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

12 James RS . A review of the thermal sensitivity of the mechanics of vertebrate skeletal muscle. J Comp Physiol B2013;183:723-733.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

13 Bishop D . Warm up I: potential mechanisms and the effects of passive warm up on exercise performance. Sports Med2003;33:439-454.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

14 Fradkin AJ , ZazrynTR, SmoligaJM. Effects of warming-up on physical performance: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Strength Cond Res2010;24:140-148.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

15 Pope RP , HerbertRD, KirwanJD, GrahamBJ. A randomized trial of preexercise stretching for prevention of lower-limb injury. Med Sci Sports Exerc2000;32:271-277.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

16 Bixler B , JonesRL. High-school football injuries: effects of a post-halftime warm-up and stretching routine. Fam Pract Res J1992;12:131-139.PubMed Google Scholar