I am delighted to announce that Bone & Joint Research (BJR), which was only established in 2012, has now received its first impact factor, which is 1.640. This is the first opportunity that the BJR has had to get an impact factor, as a journal must be registered in PubMed for at least three years. The journal impact factor is an independent measure calculated by Thomson Reuters in Philadelphia, United States and only a subset of journals are considered to be of sufficient quality to be listed by Thomson Reuters for an impact factor. The impact factors range from under 1 to over 50 (e.g. New England Journal of Medicine 55.87). Unfortunately, orthopaedic journals have relatively low impact factors, which tend to be less than 5.

In comparison, several other body systems have journals with far higher impact factors, for example, the neurological system (e.g. Nat Rev Neurosci 31.4, Annu Rev Neurosci 22.7, Trends Cogn Sci 21.1, Neuron 16) and the cardiovascular system (e.g. J Am Coll Cardiol 15.3, Circulation 14.9, Eur Heart J 14.7, Circ Res 11.1) have multiple journals with high impact factors. It is, therefore, worth reflecting as to why orthopaedic journals do not have higher impact factors.

The impact factor for a journal in a given year is calculated by dividing the number of citations, in that year, to the source items published in that journal during the previous two years, by the number of citable articles in the preceding two years. For example, the journal impact factor for Year X = (Year X citations to Year (X-1) + Year (X-2) articles)/(no. of "citable" articles published in Year (X-1) + Year (X-2)). Thus, for a citation to count towards a journal’s impact factor, it needs to be cited within two years of publication.

There are a number of factors that affect the total number of citations. The citations can be distributed evenly between the articles published, or, they can be heavily weighted to a small number of articles, which have a very high number of citations. For instance, in 2005 a study in Nature reported that 89% of the citations in its journal came from only 25% of the articles published.1 Haddad2 has listed a number of other factors that affect the number of citations, which include the number of publications in a research field; the average number of references in a paper and the type of article – reviews tend to get more citations, and scientific articles tend only to cite scientific articles, whereas clinical papers cite both clinical and preclinical articles. In addition to these factors, the citation rate is also dependent upon the number of researchers in a given field; the country of origin; the country where it is published and the language in which it is written.

Furthermore, as the impact factor does not count all citations a paper has received, but only those in the preceding two years, the vast majority of research that will quote a paper in that time period will already have been started before the cited paper is published. This makes the impact factor even more dependent on the number of researchers in a given field. Kodumuri et al3 have also pointed out the critical nature of the time period over which the citations are considered, as there is a greater lag time for surgical papers to be cited.

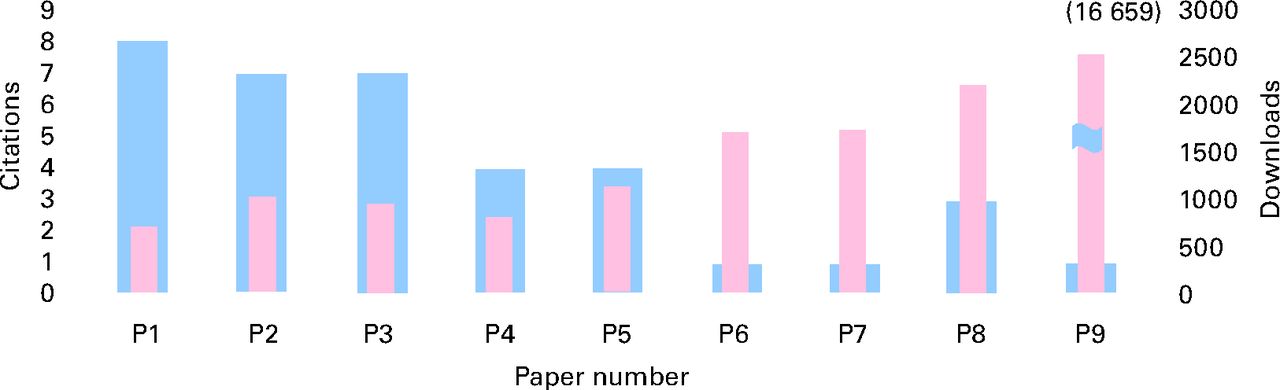

Demonstration of the impact of research is gaining increasing importance worldwide, as national funding bodies are using this to determine the allocation of central funding. Publications in journals with high impact factors are often used as a mark of this. However, different types of papers have different target audiences. For some, the paper is aimed at researchers, for others it is clinicians and for others still, policy makers. These different ‘audiences’ have different rates of citation, thus, a paper that has a message which is most relevant to practicing clinicians who do not write papers, may have a lower citation rate than a paper whose target readership is academics who, themselves, write regularly. There will be exceptions to this, such as the pivotal randomised controlled trials (RCTs), which will be read by clinicians and quoted by academics. As a consequence of this, the relationship between downloads (marker of use by clinicians, researchers and policy makers) and citations (marker of use by researchers) will not necessarily be linear. In 2014, the five most cited BJR papers4-8 from 2013 are listed in Table I and the five most downloaded BJR papers8-12 are listed in Table II. Only one paper is in both Tables (Fig. 1). As might be expected, the highly cited papers in Table I are more relevant to researchers. The highly downloaded papers were on clinical update topics that would be expected to appeal more to practicing clinicians. Although not cited greatly, the high downloads indicate that these papers appear to have had a significant impact on clinical practice.

Fig. 1

Graph showing interrelation ofcitations compared with downloads. (Number in brackets indicates actual number of downloads).

Table I

Most highly cited Bone & Joint Research papers published in 2013

| Papers | Citations (2014) | Downloads (2014) |

|---|---|---|

| Sidaginamale et al4 (P1) | 8 | 730 |

| Rodrigues-Pinto et al5 (P2) | 7 | 1042 |

| Kon et al6 (P3) | 7 | 962 |

| Goffin et al7 (P4) | 4 | 812 |

| Patel et a8 (P5) | 4 | 1139 |

Table II

Most highly downloaded Bone & Joint Research papers published in 2013

| Papers | Citations (2014) | Downloads (2014) |

|---|---|---|

| Zhang et al9 (P9) | 1 | 16 659 |

| Karlakki et al10 (P8) | 3 | 2200 |

| Ketola et al11 (P7) | 1 | 1720 |

| Johnson et al12 (P6) | 1 | 1681 |

| Patel et al8 (P5) | 4 | 1139 |

A similar picture is seen with the orthopaedic clinical journal, The Bone & Joint Journal (BJJ; formerly JBJS-Br). Only one of the five most highly cited papers13-17 in the BJJ (Table III) and the five most highly downloaded papers15,18-21 (Table IV) overlap.

Table III

Most highly cited papers in The Bone & Joint Journal published in 2013

| Papers | Citations (2014) | Downloads (2014) |

|---|---|---|

| Jenkins et al13 | 19 | 1010 |

| Chareancholvanich et al14 | 18 | 776 |

| Parvizi et al15 | 16 | 1072 |

| Zywiel et al16 | 13 | 478 |

| Gøthesen et al17 | 13 | 418 |

Table IV

Most highly downloaded papers in The Bone & Joint Journal published in 2013

| Papers | Citations (2014) | Downloads (2014) |

|---|---|---|

| Ahmad et al18 | 3 | 2860 |

| Roche and Calder19 | 1 | 2802 |

| Ibrahim et al20 | 1 | 1411 |

| Modi et al21 | 1 | 1084 |

| Parvizi et al15 | 16 | 1072 |

Sarli et al22 have also recognised that the value of publications falls into different domains; research impact, knowledge transfer, clinical implementation and community benefit. They indicate that citation analysis alone, therefore, does not assess the impact of a paper fully. For this reason, several authors have examined alternative metrics of research impact. For example, Brueton et al23 examined other ways of assessing the value of methodological research, such as the applications of a piece of work, further developments of the research, release of software and provision of guidance materials to facilitate uptake, formation of new collaborations, and broad dissemination.

Despite these concerns, the impact factor is a yardstick of a journal and an indication of quality of the review process; this is vitally important given the burgeoning number of open access journals, which do not always have the same pedigree of peer review.

1 No authors listed. Not-so-deep impact Nature2005;435:1003–1004. Google Scholar

2 Haddad FS . The impact factor: yesterday’s metric?Bone Joint J2014;96-B:289–290.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

3 Kodumuri P , OllivereB, HolleyJ, MoranCG. The impact factor of a journal is a poor measure of the clinical relevance of its papers. Bone Joint J2014;96-B:414–419.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

4 Sidaginamale RP , JoyceTJ, LordJK, et al.Blood metal ion testing is an effectivescreening tool to identify poorly performing metal-on-metal bearingsurfaces. Bone Joint Res2013;2:84–95.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

5 Rodrigues-Pinto R , RichardsonSM, HoylandJA. Identification of novel nucleus pulposus markers: interspecies variations and implications for cell-based therapiesfor intervertebral disc degeneration. Bone Joint Res2013;2:169–178.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

6 Kon E , FilardoG, Di MatteoB, PerdisaF, MarcacciM. Matrix assisted autologous chondrocyte transplantation for cartilage treatment: A systematic review. Bone Joint Res2013;2:18–25.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

7 Goffin JM , PankajP, SimpsonAHRW, SeilR, GerichTG. Does bone compaction around the helical blade of a proximal femoral nail anti-rotation (PFNA) decrease the risk of cut-out?: A subject-specific computational study. Bone Joint Res2013;2:79–83.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

8 Patel RA , WilsonRF, PatelPA, PalmerRM. The effect of smoking on bone healing: A systematic review. Bone Joint Res2013;2:102–111.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

9 Zhang Y , XuJ, WangX, et al.An in vivo study of hindfoot 3D kinetics in stage II posterior tibial tendon dysfunction (PTTD) flatfoot based on weight-bearing CT scan. Bone Joint Res2013;2:255–263.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

10 Karlakki S , BremM, GianniniS, et al.Negative pressure wound therapy for managementof the surgical incision in orthopaedic surgery: A review of evidence and mechanisms for an emerging indication. Bone Joint Res2013;2:276–284.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

11 Ketola S , LehtinenJ, RousiT, et al.No evidence of long-term benefits of arthroscopicacromioplasty in the treatment of shoulder impingement syndrome: five-year results of a randomised controlled trial. Bone Joint Res2013;2:132–139.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

12 Johnson R , JamesonSS, SandersRD, et al.Reducing surgical site infection in arthroplasty of the lower limb: A multi-disciplinary approach. Bone Joint Res2013;2:58–65.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

13 Jenkins PJ , ClementND, HamiltonDF, et al.Predicting the cost-effectiveness of total hip and knee replacement: a health economic analysis. Bone Joint J2013;95-B:115–121.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

14 Chareancholvanich K , NarkbunnamR, PornrattanamaneewongC. A prospective randomised controlled study of patient-specific cutting guides compared with conventional instrumentation in total knee replacement. Bone Joint J2013;95-B:354–359.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

15 Parvizi J , GehrkeT, ChenAF. Proceedings of the International Consensus on Periprosthetic Joint Infection. Bone Joint J2013;95-B:1450–1452.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

16 Zywiel MG , Brandt J-M, OvergaardCB, et al.Fatal cardiomyopathy after revision total hip replacement for fracture of a ceramic liner. Bone Joint J2013;95-B:31–37.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

17 Gøthesen O , EspehaugB, HavelinL, et al.Survival rates and causes of revision in cemented primary total knee replacement: a report from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register 1994-2009. Bone Joint J2013;95-B:636–642.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

18 Ahmad Z , SiddiquiN, MalikSS, et al.Lateral epicondylitis: A review of pathology and management. Bone Joint J2013;95-B:1158–1164.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

19 Roche AJ , CalderJDF. Achilles tendinopathy: A review of the current concepts of treatment. Bone Joint J2013;95-B:1299–1307.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

20 Ibrahim MS , TwaijH, GiebalyDE, NizamI, HaddadFS. Enhanced recovery in total hip replacement: a clinical review. Bone Joint J2013;95-B:1587–1594.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

21 Modi CS , BeazleyJ, ZywielMG, LawrenceTM, VeilletteCJH. Controversies relating to the management of acromioclavicular joint dislocations. Bone Joint J2013;95-B:1595–1602.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

22 Sarli CC , DubinskyEK, HolmesKL. Beyond citation analysis: a model for assessment of research impact. J Med Libr Assoc2010;98:17–23.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

23 Brueton VC , ValeCL, Choodari-OskooeiB, JinksR, TierneyJF. Measuring the impact of methodological research: a framework and methods to identify evidence of impact. Trials2014;15:464.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar