Abstract

Objectives

To define Patient Acceptable Symptom State (PASS) thresholds for the Oxford hip score (OHS) and Oxford knee score (OKS) at mid-term follow-up.

Methods

In a prospective multicentre cohort study, OHS and OKS were collected at a mean follow-up of three years (1.5 to 6.0), combined with a numeric rating scale (NRS) for satisfaction and an external validation question assessing the patient’s willingness to undergo surgery again. A total of 550 patients underwent total hip replacement (THR) and 367 underwent total knee replacement (TKR).

Results

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves identified a PASS threshold of 42 for the OHS after THR and 37 for the OKS after TKR. THR patients with an OHS ≥ 42 and TKR patients with an OKS ≥ 37 had a higher NRS for satisfaction and a greater likelihood of being willing to undergo surgery again.

Conclusions

PASS thresholds appear larger at mid-term follow-up than at six months after surgery. With- out external validation, we would advise against using these PASS thresholds as absolute thresholds in defining whether or not a patient has attained an acceptable symptom state after THR or TKR.

Cite this article: Bone Joint Res 2014;3:7–13.

Article focus

Patient Acceptable Symptom State (PASS) thresholds define whether a patient has achieved an acceptable level of functioning after an intervention, such as hip or knee replacement

Contrary to Minimal Clinically Important Differences, in PASS the outcome is of interest, instead of the extent of improvement

Key messages

PASS thresholds are time-dependent

External criteria, such as a numerical rating scale for satisfaction or validation questions, which have been shown to be related to patient satisfaction after joint replacement, can be employed to validate PASS thresholds

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of our study is the validation of the PASS thresholds using two different external criteria

The main weakness of our study is the absence of a pre-operative measurement of the Oxford hip (OHS) and knee scores (OKS)

Introduction

Several distinct types of outcome measures are of interest in orthopaedic surgery. The time to a certain event, such as revision surgery, has historically been the principal outcome of interest in joint replacement patients.1,2 In recent years, patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) have become popular, allowing the assessment of the clinical outcome of joint replacement from the patient’s perspective.3 PROMs can be summarised in numerous ways. In the orthopaedic literature, mean scores of the study population are frequently presented. The mean pre-operative score provides information on the ‘average’ patient before surgery. Similarly, the mean post-operative score provides information on the ‘average’ patient after surgery, and the mean change in these scores provides information on the improvement (or deterioration) experienced by the ‘average’ patient, who does improve substantially after joint replacement.4 However, a large proportion of joint replacement patients suffer from persisting pain, or are dissatisfied with the surgical results.5-7 Data regarding the mean improvement after joint replacement mainly report the improvement of many patients with successful outcomes, but can neglect patients with suboptimal outcomes, making it of limited use for individual patients encountered in clinical practice.

Patient Acceptable Symptom States (PASS) and Minimal Clinically Important Differences (MCIDs) are two complementary constructs, which allow a more individualised approach to the analysis of PROMs.8-10 PASS is defined as an outcome score threshold of the post-operative score, above which a patient is defined as experiencing a satisfactory outcome, and below which an unsatisfactory outcome is experienced. MCID is defined as the minimum amount of improvement between pre- and post-operative scores that a patient should experience after a specific intervention in order to have achieved a minimally important difference. PASSs and MCIDs allow estimation of the probability of a satisfactory outcome or a relevant improvement. These probabilities are relevant for individual patients, encountered in clinical practice, who either do or do not achieve an acceptable state or experience a relevant improvement.11

Recently, PASSs have been estimated for the Oxford hip score (OHS)12 and Oxford knee score (OKS)13 at short-term follow-up.14 An important issue is whether the chosen follow-up period of six months after joint replacement is adequate. A recent systematic review has suggested that patients may not have fully recovered at six months after THR.15 Thresholds that define whether or not patients have achieved an acceptable symptom state, such as the PASS, may therefore differ between patients who are still recovering from their surgery and patients who have recovered fully. Therefore, we questioned whether PASS thresholds are different at mid-term compared with short-term follow-up. We questioned whether the OHS and OKS are correlated to patient satisfaction at mid-term follow-up. Additionally, we questioned whether responders (i.e., patients who have an acceptable symptom state according to the PASS) are more satisfied than non-responders. Finally, we questioned whether responders were more likely to be willing to undergo surgery again, compared with non-responders.

Materials and Methods

The current study is part of a multicentre cohort study of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) after THR/TKR (NTR2190), performed from August 2010 to August 2011.16-20 Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from all participating centres and all patients gave written informed consent (CCMO-Nr: NL29018.058.09; MEC-Nr: P09.189). It concerned the clinical follow-up of a multi-centre randomised controlled clinical trial, comparing the use of the drug erythropoietin and two re-infusion techniques of autologous blood in order to decrease allogenic blood transfusions (Netherlands Trial Register: NTR303). In this trial, 2442 primary and revision hip or knee replacements in 2257 patients were included between 2004 and 2009. All patients who participated in the randomised controlled trial completed pre-operative HRQoL questionnaires, underwent primary THR or TKR and who were alive at the time of inclusion for the present follow-up study, were eligible for inclusion. The first joint replacement was selected for inclusion in the follow-up study for patients who participated more than once in the previous study. Records of the financial administration of all participating centres were checked in order to ascertain that all eligible patients were alive before being approached by the first author (JCK). For the present follow-up study, all eligible patients were first sent an invitation letter signed by their treating orthopaedic surgeon, an information brochure and a reply card. Patients who indicated that they were willing to participate were sent a questionnaire. Patients who did not respond to the first invitation within four weeks were sent another invitation letter. Those who did not respond to this second invitation were contacted by telephone by the first author. Patients who did not return their questionnaire within four weeks were also contacted by telephone by the first author. The data used in this report constitute a subset of patients who completed post-operative questionnaires.

Outcome measures

We measured the overall satisfaction with the outcome of surgery on a numeric rating scale (NRS), which ranged from 0 (extremely dissatisfied) to 10 (extremely satisfied).16,17 We added a validation question to the questionnaire, which took the following form: “Knowing what your hip or knee replacement surgery did for you, would you still have undergone this surgery?”, with dichotomous answers of ‘yes’ vs ‘no’. This validation question was previously used in a similar validation study of clinically important differences after THR and TKR.21

Joint-specific PROMs were measured using the OHS for THR patients and the OKS for patients undergoing TKR, both of which were translated and validated in Dutch.22,23 Each questionnaire comprises 12 questions regarding pain and functioning of the hip or knee during the previous four weeks. Each question is answered on a five-point Likert scale, and an overall score is calculated by summarising the responses to each of the 12 questions. This sum score ranges from 0 to 48, where 0 indicates the most severe symptoms and 48 the least severe symptoms.

Potential confounders included age at joint replacement, gender, body mass index (BMI), indication for joint replacement (osteoarthritis (OA) vs other), patient-reported Charnley classification of comorbidity24,25 (A, patients in which the index operated hip or knee are affected only; B, patients in which the other hip or knee is affected as well; C, patients with a hip or knee replacement and other affected joints and/or a medical condition which affects the patients’ ability to ambulate) and pre-operative HRQoL. HRQoL was measured pre-operatively using the Short-Form (SF-)36,26 which is translated and validated in the Dutch language.27 The 36 items cover eight domains (physical function, role physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social function, role emotional, and mental health), for which a sub-scale score is calculated (100 indicating no symptoms and 0 indicating extreme symptoms). These sub-scales can be summarised in a physical component summary (PCS) and a mental component summary (MCS).

Statistical analysis

We performed descriptive analyses of the patients’ baseline characteristics. All analyses were performed separately for THR and TKR, as MCIDs have been shown to differ considerably between these surgical interventions.28 The correlation between OHS or OKS and NRS for satisfaction was calculated using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were used to identify thresholds for OHS/OKS scores at mid-term follow-up, which are associated with an acceptable level of patient satisfaction with joint replacement. An acceptable level of patient satisfaction was defined as a NRS for satisfaction ≥ 5, which is the equivalent of a visual analogue scale satisfaction score ≥ 50.3,29 This particular threshold has been used previously to compare satisfied and dissatisfied patients after joint replacement.14 The chosen PASS thresholds were equivalent to the point at which sensitivity and specificity were closest.30 The 95% confidence intervals (CI) around the thresholds were estimated using percentile bootstrap methods, based on 1000 random samples with replacement from the original data. In order to explore whether the found thresholds are consistent across subgroups, we identified separate thresholds for subgroups based on the following variables: length of follow-up (< 3 years vs ≥ 3 years), gender, age (< 70 years vs ≥ 70 years), BMI (< 30 kg/m2vs ≥ 30 kg/m2), Charnley classification (A/B vs C), SF-36 PCS (< 50 vs ≥ 50) and SF-36 MCS (< 50 vs ≥ 50).

Based on the overall PASS thresholds, we divided patients into responders (those with an OHS or OKS ≥ the PASS threshold) and non-responders (OHS/OKS < PASS threshold). We compared the mean NRS for satisfaction between responders and non-responders separately for THR and TKR patients, using three different models. In the first model, we calculated the mean NRS for satisfaction of all responders and the mean NRS of all non-responders, stratified by centre. In the second model, we performed linear mixed model regression analyses, with age and gender as fixed effects and the centre as a random effect, while stratifying for quartile of follow-up length. The final model consisted of linear mixed model regression analyses, with age, gender, BMI, Charnley classification, indication (OA vs other), and pre-operative SF-36 PCS and MCS as fixed effects and the centre as a random effect, while stratifying for quartile of follow-up length.

Finally, we compared the odds of responding the validation question positively between responders and non-responders, using three different models. In the first model, we calculated crude odds ratios. In the second model, we performed logistic mixed model regression analyses, with age and gender as fixed effects and the centre as a random effect, while stratifying for quartile of follow-up length. In the final model, we performed logistic mixed model regression analyses, with age, gender, BMI, Charnley classification, indication (OA vs other), and pre-operative SF-36 PCS and MCS as fixed effects and the centre as a random effect, while stratifying for quartile of follow-up length.

All analyses were performed using R v2.14.1.31

Results

A total of 550 patients underwent THR and 367 underwent TKR. Patient characteristics are described in Table I. The mean follow-up was similar for THR and TKR patients, at 3.2 years (1.5 to 6.0) and 3.2 years (1.3 to 6.0), respectively. THR patients were slightly younger at joint replacement surgery than TKR patients. The proportion of males was similar. TKR were more often obese or morbidly obese. The majority of THR and TKR patients underwent joint replacement for primary OA.

Table I

Patient characteristics (THR, total hip replacement; TKR, total knee replacement)

| Characteristic* | Primary THR (n = 550) | Primary TKR (n = 367 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean follow-up (yrs) (sd; range) | 3.2 (1.1; 1.5 to 6.0) | 3.2 (1.1; 1.3 to 6.0) | |

| Mean (sd) age at operation (yrs) | 65.9 (10.5) | 68.7 (9.6) | |

| Male (n, %) | 188 (34.2) | 122 (33.3) | |

| Body mass index group at follow-up (n, %) | |||

| < 25 kg/m2 | 182 (34.3)62 (17.9) | ||

| 25 to 29 kg/m2 | 226 (42.6) | 154 (44.5) | |

| 30 to 34 kg/m2 | 94 (17.7) | 81 (23.4) | |

| > 35 kg/m2 | 28 (5.8) | 49 (14.2) | |

| Indication for arthroplasty (n, %) | |||

| Osteoarthritis | 471 (86.3) | 323 (89.0) | |

| Patient-reported Charnley classification at follow-up (n, %) | |||

| A | 119 (23.1) | 49 (13.9) | |

| B | 74 (14.3) | 36 (10.2) | |

| C | 323 (62.6) | 267 (75.9) | |

| Median pre-operative SF-36 scores (IQR) | |||

| Physical component summary | 39.8 (34.1 to 45.3) | 41.3 (35.0 to 47.3) | |

| Mental component summary | 54.8 (45.6 to 60.0) | 54.1 (45.4 to 59.1) | |

-

* SF-36, Short-Form 36; IQR, interquartile range

The mean and median OHS scores at mid-term follow-up were 41.5 (sd 7.93) and 44 (interquartile range (IQR) 39 to 47), respectively. The mean NRS for satisfaction was 8.55 (sd 2.19) and 94.7% (521 of 550) of all THR patients were satisfied (defined as NRS ≥ 5). The mean and median OKS scores at mid-term follow-up were 39.1 (sd 9.04) and 42 (IQR 35 to 46), respectively. The mean NRS for satisfaction was 8.07 (sd 2.61) and 90.7% (333 of 367) of all TKR patients were satisfied.

The NRS correlated with both the OHS (Pearson correlation coefficient 0.52 (95% CI 0.46 to 0.58)) and the OKS (Pearson correlation coefficient 0.64 (95% CI 0.57 to 0.69)), indicating a large correlation.

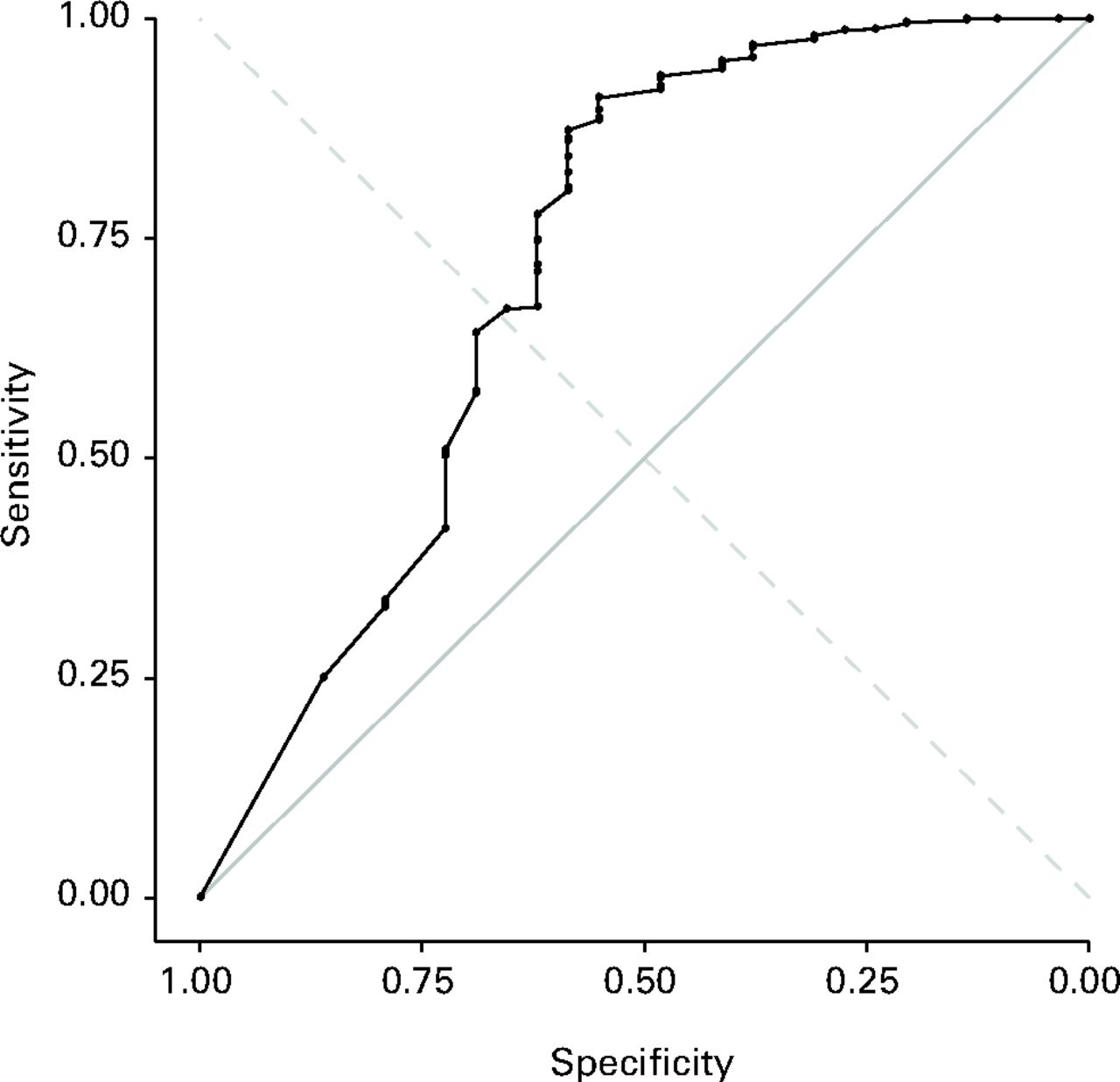

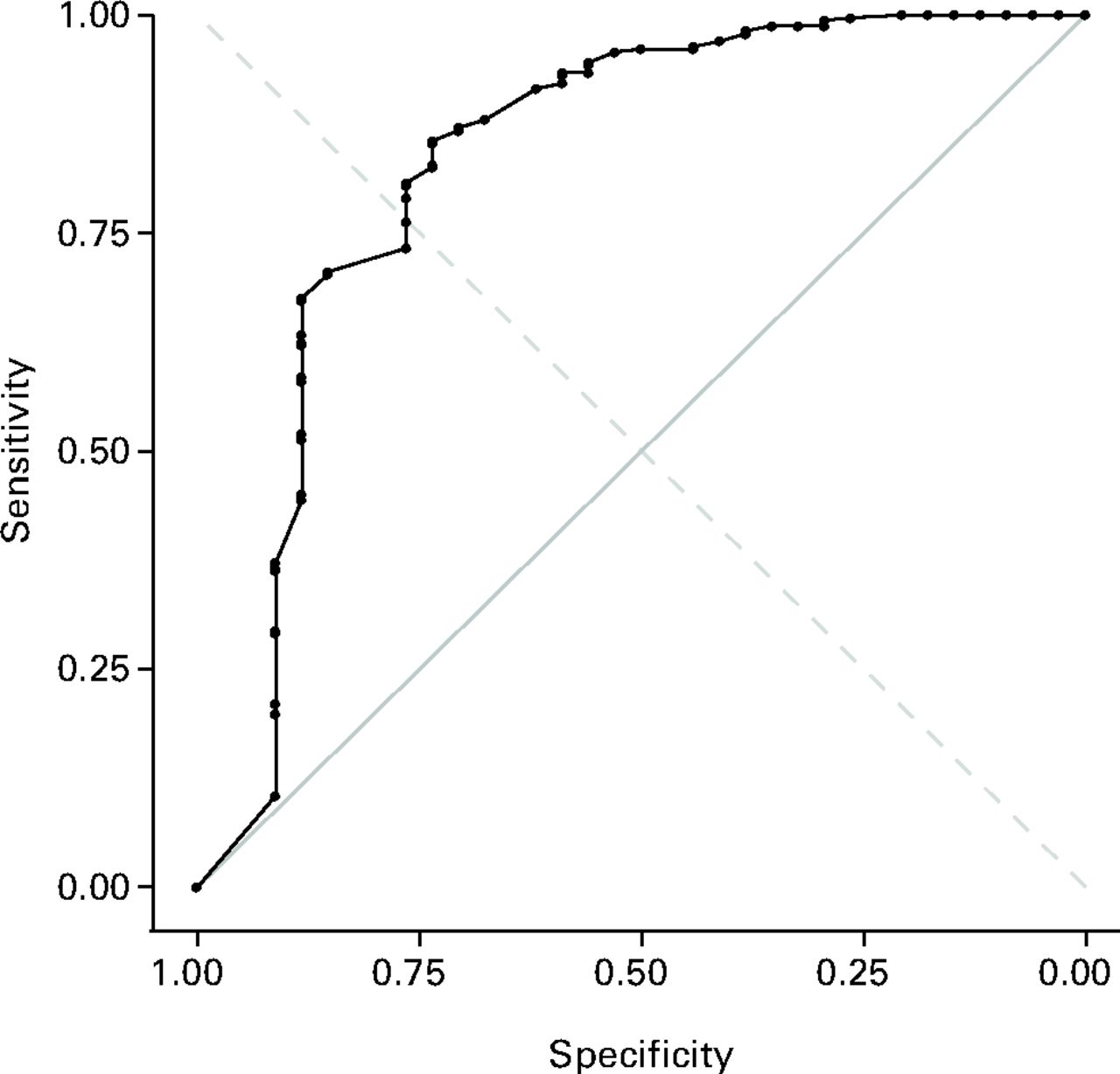

ROC curves of OHS thresholds and OKS thresholds are shown in Figures 1 and 2. The OHS ROC curve revealed a PASS threshold of 42, with a sensitivity of 67.0% and a specificity of 65.5%. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) was 0.72 (95% CI 0.60 to 0.84). The OKS ROC curve revealed a PASS threshold of 37, with a sensitivity of 76.3% and a specificity of 76.5%. The AUC was 0.83 (95% CI 0.74 to 0.93). ROC curves of subgroups showed variation in the thresholds found (Tables II and III). The variation appears larger in OHS thresholds than in OKS thresholds.

Fig. 1

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve to establish a threshold for the mid-term follow-up Oxford hip score associated with mid-term satisfaction with surgery. Sensitivity (67.0%) and specificity (65.5%) are in equilibrium when a threshold of 42 points is chosen. The area under ROC curve (AUC) was 0.72 (95% confidence interval 0.60 to 0.84).

Fig. 2

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve to establish a threshold for the mid-term follow-up Oxford hip score associated with mid-term satisfaction with surgery. Sensitivity (76.3%) and specificity (76.5%) are in equilibrium when a threshold of 37 points is chosen. The area under ROC curve (AUC) was 0.83 (95% confidence interval 0.74 to 0.93).

Table II

Patient acceptable symptom state (PASS) score thresholds for mid-term follow-up Oxford hip score and proportion of patients classified as reaching a satisfactory symptom state (CI, confidence interval)

| Parameter* | Threshold value (95% CI) | Satisfactory symptom state (n, %) |

|---|---|---|

| Entire population | 42 (38.5 to 44.2) | 359 (65.3) |

| Follow-up | ||

| < 3 years | 45 (39.6 to 46.5) | 134 (47.2) |

| ≥ 3 years | 39 (30.5 to 42.5) | 184 (69.2) |

| Gender | ||

| Males | 47 (44.2 to 47.5) | 85 (45.2) |

| Females | 38 (30.5 to 41.2) | 258 (71.3) |

| Age | ||

| < 70 years | 44 (39.1 to 45.5) | 204 (60.0) |

| ≥ 70 years | 40 (30.5 to 42.5) | 127 (60.5) |

| BMI | ||

| < 30 kg/m2 | 43 (39.6 to 45.5) | 280 (68.6) |

| ≥ 30 kg/m2 | 36 (25.5 to 43.5) | 55 (45.1) |

| Charnley class | ||

| A and B | 45 (26.0 to 47.5) | 150 (77.7) |

| C | 41 (37.0 to 43.5) | 177 (54.8) |

| SF-36 PCS | ||

| < 50 | 43 (37.5 to 44.7) | 287 (64.8) |

| ≥ 50 | 47 (34.0 to 48.0) | 94 (90.0) |

| SF-36 MCS | ||

| < 50 | 38 (28.7 to 41.5) | 94 (54.0) |

| ≥ 50 | 45 (40.7 to 46.5) | 156 (48.3) |

-

* BMI, body mass index; SF-36 P-/MCS, Short-Form 36 Physical/Mental Component Summary

Table III

Patient acceptable symptom state (PASS) score thresholds for mid-term follow-up Oxford knee score and proportion of patients classified as reaching a satisfactory symptom state (CI, confidence interval)

| Parameter* | Threshold value (95% CI) | Satisfactory symptom state (n, %) |

|---|---|---|

| Entire population | 37 (31.8 to 38.5) | 271 (73.8) |

| Follow-up | ||

| < 3 years | 34 (29.7 to 37.5) | 144 (78.7) |

| ≥ 3 years | 38 (32.5 to 41.5) | 131 (74.0) |

| Gender | ||

| Males | 39 (33.5 to 44.4) | 89 (73.6) |

| Females | 33 (30.5 to 37.5) | 171 (70.7) |

| Age | ||

| < 70 years | 34 (29.7 to 38.1) | 139 (77.7) |

| ≥ 70 years | 38 (31.3 to 41.7) | 140 (77.3) |

| BMI | ||

| < 30 kg/m2 | 38 (32.0 to 39.5) | 170 (78.7) |

| ≥ 30 kg/m2 | 35 (29.7 to 40.5) | 84 (64.6) |

| Charnley class | ||

| A and B | 39 (30.8 to 45.5) | 53 (62.4) |

| C | 36 (30.5 to 38.5) | 180 (67.4) |

| SF-36 PCS | ||

| < 50 | 35 (31.3 to 38.5) | 172 (63.2) |

| ≥ 50 | 39 (25.0 to 47.0) | 23 (39.0) |

| SF-36 MCS | ||

| < 50 | 33 (21.5 to 38.5) | 108 (86.4) |

| ≥ 50 | 38 (33.5 to 42.3) | 147 (71.4) |

-

* BMI, body mass index; SF-36 P-/MCS, Short-Form 36 Physical/Mental Component Summary

The mean NRS for satisfaction was significantly higher in responders than in non-responders, both for THR and TKR (Table IV). Both models showed a mean difference between responders and non-responders of approximately two points for THR patients and three points for TKR patients. Responders were more likely to be willing to undergo surgery again (Table V). All models showed odds ratios of approximately 7, indicating a seven-times higher odds of willingness to undergo surgery again in responders versus non-responders, while controlling for confounding (Table V).

Table IV

Comparison of mean numerical rating scale (NRS) for satisfaction between responders and non-responders according to the Patient Acceptable Symptom State (PASS) score thresholds for total hip (THR) and total knee replacement (TKR)

| Mean NRS for satisfaction | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Procedure | Responders (95% CI) | Non-responders (95% CI) | Mean difference adjusted for age and gender* (95% CI) | Mean difference adjusted for all potential confounders† (95% CI) |

| THR | 9.28 (9.26 to 9.29) | 7.26 (7.22 to 7.31) | 1.89 (1.53 to 2.25) | 1.87 (1.47 to 2.26) |

| TKR | 9.04 (9.01 to 9.06) | 6.78 (6.71 to 6.84) | 2.89 (2.40 to 3.38) | 2.96 (2.44 to 3.48) |

-

* stratified by quartiles of follow-up length † adjusted for age, gender, body mass index, Charnley classification, indication (osteoarthritis vs other), pre-operative, Short-Form 36 physical and mental component summaries and stratified by quartiles of follow-up length

Table V

Comparison of willingness to undergo surgery again between responders and non-responders according to the Patient Acceptable Symptom State (PASS) score thresholds for total hip (THR) and total knee replacement (TKR). An odds ratio (OR) > 1 indicates a higher odds of willingness to undergo surgery again in responders compared with non-responders (CI, confidence interval)

| Procedure | Crude OR (95% CI) | OR adjusted for age and gender* (95% CI) | OR adjusted for all potential confounders† (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| THR | 7.64 (4.09 to 15.3) | 6.97 (3.51 to 13.8) | 8.53 (3.80 to 19.1) |

| TKR | 7.28 (3.85 to 14.3) | 7.92 (3.79 to 16.6) | 7.73 (2.84 to 21.0) |

-

* stratified by quartiles of follow-up length † adjusted for age, gender, body mass index, Charnley classification, indication (osteoarthritis vs other), pre-operative Short-Form 36 physical and mental component summaries, and stratified by quartiles of follow-up length

Discussion

PASS thresholds for the OHS and OKS are considerably higher at mid-term follow-up than those at six months post-operatively. The multiple approaches in validating the PASS thresholds and the rigorous efforts to minimise confounding are the main strengths of this study. All approaches show that the thresholds of 42 points for the OHS and 37 points for the OKS can discriminate between successful and less successful patient outcomes after THR or TKR in this study population, according to the overall satisfaction assessment and the willingness to undergo surgery again.

A limitation of our study is that we did not measure the OHS or OKS pre-operatively. Consequently, we could not investigate whether the PASS thresholds are valid across strata of baseline OHS or OKS scores. As a surrogate measurement of pre-operative joint functioning, we investigated differences in PASS thresholds in strata of the pre-operative physical and mental component summaries of the SF-36, which only had a small effect. Furthermore, other evidence from the same research group suggests that baseline OHS or OKS values are poor predictors of overall patient satisfaction with the outcome of the joint replacement.14,32

Another limitation of our study is the broad range in follow-up length. In order to account for this range, we stratified our analysis per quartile of follow-up period. Although a residual effect of follow-up length cannot be excluded, we do not think this is very plausible, as recent evidence suggests that after full recovery has taken place, the improvement in joint function is sustained throughout mid-term follow-up.33

Demographically, our study population is similar to that of Judge et al.14 Cultural differences cannot be excluded from explaining the differences found in PASS thresholds, although this is unlikely, given the resemblance of English and Dutch urban joint replacement patients. A more plausible explanation could be the difference in physical recovery. Patients who are fully recovered at mid-term follow-up could be less prone to be satisfied with lower OHS or OKS scores, as the probability of further improvement in physical functioning is small. Six months after joint replacement, patients might be more readily satisfied with suboptimal OHS or OKS scores, as the speed of recovery is quite high.

Conceptually, MCIDs and PASSs are complementary. Both approach an individual patient’s health state, but from a slightly different angle. In MCIDs, the emphasis is on whether or not an individual has improved after a certain therapy.34 In PASSs, the emphasis is on whether or not the achieved outcome is acceptable from the patients perspective.34 Both MCIDs and PASS have gained in interest recently.28,35-37 PASS might be more important than the MCID, as Dougados38 phrased eloquently: “It’s good to feel better but it’s better to feel good.” Similar methodological difficulties are encountered both in MCIDs and PASSs: both approaches lead to a loss of power compared with the population-level mean difference, both approaches depend on population and contextual characteristics and there is no clear consensus on the optimal statistical approach.8,10,39 Despite these difficulties, MCIDs and PASSs are the best tools available to analyse PROM data at the individual level.

In this study, we estimated PASS in OHS/OKS at mid-term follow-up in a Dutch population. We found evidence suggesting that PASSs are time-dependent. Besides being time-dependent, PASS might also be population-dependent, as different sub-groups had different PASS thresholds. Without any form of external validation at a similar follow-up period, we would advise against using these PASS thresholds as absolute thresholds in defining whether or not a patient has attained an acceptable symptom state after THR/TKR.

Supplementary material

Two figures describing the relationship between Oxford Score and numerical rating scale, and two tables detailing response to Oxford Score by centre for both operations, are available alongside this article.

1 Keurentjes JC , FioccoM, SchreursBW, et al.Revision surgery is overestimated in hip replacement. Bone Joint Res2012;1:258–262.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

2 Nouta KA, Pijls BG, Fiocco M, Keurentjes JC, Nelissen RG. How to deal with lost to follow-up in total knee arthroplasty: a new method based on the competing risks approach. Int Orthop 2013:Epub. Google Scholar

3 Arden NK , KiranA, JudgeA, et al.What is a good patient reported outcome after total hip replacement?Osteoarthritis Cartilage2011;19:155–162.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

4 Ethgen O , BruyèreO, RichyF, DardennesC, ReginsterJY. Health-related quality of life in total hip and total knee arthroplasty: a qualitative and systematic review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]2004;86-A:963–974. Google Scholar

5 Beswick AD , WyldeV, Gooberman-HillR, BlomA, DieppeP. What proportion of patients report long-term pain after total hip or knee replacement for osteoarthritis?: a systematic review of prospective studies in unselected patients. BMJ Open2012;2:000435. Google Scholar

6 Nilsdotter AK , Toksvig-LarsenS, RoosEM. Knee arthroplasty: are patients’ expectations fulfilled?: a prospective study of pain and function in 102 patients with 5-year follow-up. Acta Orthop2009;80:55–61. Google Scholar

7 Scott CE , BuglerKE, ClementND, et al.Patient expectations of arthroplasty of the hip and knee. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]2002;94-B:974–981.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

8 Tubach F , WellsGA, RavaudP, DougadosM. Minimal clinically important difference, low disease activity state, and patient acceptable symptom state: methodological issues. J Rheumatol2005;32:2025–2029.PubMed Google Scholar

9 Tubach F , RavaudP, BaronG, et al.Evaluation of clinically relevant states in patient reported outcomes in knee and hip osteoarthritis: the patient acceptable symptom state. Ann Rheum Dis2005;64:34–37.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

10 Revicki D , HaysRD, CellaD, SloanJ. Recommended methods for determining responsiveness and minimally important differences for patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol2008;61:102–109.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

11 Singh J , SloanJA, JohansonNA. Challenges with health-related quality of life assessment in arthroplasty patients: problems and solutions. J Am Acad Orthop Surg2010;18:72–82.PubMed Google Scholar

12 Dawson J , FitzpatrickR, CarrA, MurrayD. Questionnaire on the perceptions of patients about total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]1996;78-B:185–190.PubMed Google Scholar

13 Dawson J , FitzpatrickR, MurrayD, CarrA. Questionnaire on the perceptions of patients about total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]1998;80-B:63–69.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

14 Judge A , ArdenNK, KiranA, et al.Interpretation of patient-reported outcomes for hip and knee replacement surgery: identification of thresholds associated with satisfaction with surgery. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]2012;94-B:412–418.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

15 Vissers MM , BussmannJB, VerhaarJAN, et al.Recovery of physical functioning after total hip arthroplasty: systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Phys Ther2011;91:615–629.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

16 Keurentjes JC , FioccoM, So-OsmanC, et al.Patients with severe radiographic osteoarthritis have a better prognosis in physical functioning after hip and knee replacement: a cohort-study. PLoS One2013;8:59500.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

17 Keurentjes JC , BlaneD, BartleyM, et al.Socio-economic position has no effect on improvement in health-related quality of life and patient satisfaction in total hip and knee replacement: a cohort study. PLoS One2013;8:56785.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

18 Keurentjes JC, Fiocco M, Nelissen RG. Willingness to undergo surgery again validated clinically important differences in health-related quality of life after total hip replacement or total knee replacement surgery. J Clin Epidemiol 2013:Epub. Google Scholar

19 Evangelou E, Kerkhof HJ, Styrkarsdottir U, et al. A meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies identifies novel variants associated with osteoarthritis of the hip. Ann Rheum Dis 2013:Epub. Google Scholar

20 Keurentjes JC , FioccoM, So-OsmanC, et al.Hip and knee replacement patients prefer pen-and-paper questionnaires Implications for future patient-reported outcome measure studies. Bone Joint Res2013;2:238–244. Google Scholar

21 Chesworth BM , MahomedNN, BourneRB, DavisAM. Willingness to go through surgery again validated the WOMAC clinically important difference from THR/TKR surgery. J Clin Epidemiol2008;61:907–918.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

22 Gosens T , HoefnagelsNH, de VetRC, et al.The “Oxford Heup Score”: the translation and validation of a questionnaire into Dutch to evaluate the results of total hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop2005;76:204–211. Google Scholar

23 Haverkamp D , BreugemSJM, SiereveltIN, BlankevoortL, van DijkCN. Translation and validation of the Dutch version of the Oxford 12-item knee questionnaire for knee arthroplasty. Acta Orthop2005;76:347–352.PubMed Google Scholar

24 Dunbar MJ , RobertssonO, RydL. What’s all that noise?: the effect of co-morbidity on health outcome questionnaire results after knee arthroplasty. Acta Orthop Scand2004;75:119–126. Google Scholar

25 Charnley J . The long-term results of low-friction arthroplasty of the hip performed as a primary intervention. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]1972;54-B:61–76.PubMed Google Scholar

26 Ware J. SF-36 health survey: manual and interpretation guide. Boston: The Health Institute New England Medical Center, 1993. Google Scholar

27 Aaronson NK , MullerM, CohenPD, et al.Translation, validation, and norming of the Dutch language version of the SF-36 Health Survey in community and chronic disease populations. J Clin Epidemiol1998;51:1055–1068.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

28 Keurentjes JC , Van TolFR, FioccoM, SchoonesJ, NelissenR. Minimal clinically important differences in health-related quality of life after total hip or knee replacement: a systematic review. Bone Joint Res2012;1:71–77. Google Scholar

29 Baker PN , van der MeulenJH, LewseyJ, GreggPJ. The role of pain and function in determining patient satisfaction after total knee replacement: data from the National Joint Registry for England and Wales. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]2007;89-B:893–900. Google Scholar

30 Farrar JT , YoungJP, LaMoreauxL, WerthJL, PooleRM. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain2001;94:149–158.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

31 No authors listed. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2008. Google Scholar

32 Judge A , ArdenNK, PriceA, et al.Assessing patients for joint replacement: can pre-operative Oxford hip and knee scores be used to predict patient satisfaction following joint replacement surgery and to guide patient selection?J Bone Joint Surg [Br]2011;93-B:1660–1664.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

33 Ng CY , BallantyneJA, BrenkelIJ. Quality of life and functional outcome after primary total hip replacement: a five-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]2007;89-B:868–873. Google Scholar

34 Kvien TK , HeibergT, Hagen KrB. Minimal clinically important improvement/difference (MCII/MCID) and patient acceptable symptom state (PASS): what do these concepts mean?Ann Rheum Dis2007;66(Suppl 3):40–41.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

35 Clement ND, Macdonald D, Simpson AH. The minimal clinically important difference in the Oxford knee score and Short Form 12 score after total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2013:Epub. Google Scholar

36 Paulsen A, Roos EM, Pedersen AB, Overgaard S. Minimal clinically important improvement (MCII) and patient-acceptable symptom state (PASS) in total hip arthroplasty (THA) patients 1 year postoperatively. Acta Orthop 2013:Epub. Google Scholar

37 Browne JP , van der MeulenJH, LewseyJD, LampingDL, BlackN. Mathematical coupling may account for the association between baseline severity and minimally important difference values. J Clin Epidemiol2010;63:865–874.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

38 Dougados M . It’s good to feel better but it’s better to feel good. J Rheumatol2005;32:1–2. Google Scholar

39 Jaeschke R , SingerJ, GuyattGH. Measurement of health status: ascertaining the minimal clinically important difference. Control Clin Trials1989;10:407–415. Google Scholar

Funding statement:

Ongoing research grant of the Dutch Arthritis Association to Professor R. G. H. H Nelissen, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Leiden University Medical Center: grant number LLP-013 (http://www.reumafonds.nl/informatie-voor-doelgroepen/professionals/ongoing-research). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author contributions:

J. C. Keurentjes: Study conception and design, Data collection, Data analysis, Drafting of the article

F. R. Van Tol: Data collection, Drafting of the article, Critical revision of the article

M. Fiocco: Study conception and design, Data analysis, Critical revision of the article

C. So-Osman: Study conception and design, Data collection, Drafting of the article, Critical revision of the article

R. Onstenk: Data collection, Drafting of the article, Critical revision of the article

A. W. M. M. Koopman-Van Gemert: Data collection, Drafting of the article, Critical revision of the article

R. G. Pöll: Data collection, Drafting of the article, Critical revision of the article

R. G. H. H. Nelissen: Study conception and design, Data collection, Drafting of the article, Critical revision of the article

ICMJE Conflict of Interest:

None declared

©2014 The British Editorial Society of Bone & Joint Surgery. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attributions licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, but not for commercial gain, provided the original author and source are credited.