Abstract

The “Universal Protocol” (UP) was launched as a regulatory compliance standard by the Joint Commission on 1st July 1 2004, with the primary intent of reducing the occurrence of wrong-site and wrong-patient surgery. As we’re heading into the tenth year of the UP implementation in the United States, it is time for critical assessment of the protocol’s impact on patient safety related to the incidence of preventable never-events. This article opens the debate on the potential shortcomings and pitfalls of the UP, and provides recommendations on how to circumvent specific inherent vulnerabilities of this widely established patient safety protocol.

Despite the widespread implementation of surgical safety checklists, including the WHO ‘Safe Surgery Saves Lives‘ checklist,1 the‘Surgical Patient Safety System‘ (SURPASS) checklist,2,3 and the Universal Protocol (UP),4,5 general compliance appears poor and we are still awaiting the promised dramatic impact in the global reduction of preventable adverse events and surgical complication rates.6-10 This article was designed to outline “pitfalls and pearls” of the Joint Commission’s UP at the time of its tenth year after formal implementation in the United States.

The ‘Universal Protocol’ (UP)

The UP was initially designed to ensure correct patient identity, correct intended procedure, and surgery performed at the correct surgical site.11,12

In essence, the UP consists of a pre-procedure verification process, surgical site marking and surgical ‘time out’ immediately prior to initiating a procedure. While the pre-procedure verification process and surgical site marking are usually performed in the pre-operative holding area, the ‘time out’ is accomplished in the operating room before the surgical procedure.13,14 All three steps of the UP are dedicated to ensuring correct patient identity, correct intended procedure, and correct surgical site. The ‘time out’ was later expanded to include the verification of correct patient positioning, availability of relevant documents, diagnostic images, instruments and implants, and the need for pre-operative antibiotics and other essential medications, e.g. the use of beta-blockers.15 Of note, the UP also applies to any interventional setting outside the operating room, for invasive procedures requiring patients’ written informed consent.

Wrong-site surgery: is the ‘horror’ finally over?

The US National Quality Forum (NQF) defines wrong-site and wrong-patient procedures as “serious reportable surgical events” which should theoretically ‘never’ occur (Table I).16 However, despite the widespread implementation of the UP since July 1 2004, recurring reports document the continued occurrence of wrong-site and wrong-patient procedures in the United States.10,17-21 Clarke et al12 published an analysis of hospital reports on reported wrong-site, wrong-patient, and wrong-procedure surgery in the state of Pennsylvania during a 30-month period from 2004 to 2006.12 The authors detected 427 reports of wrong-site occurrences, of which 56% were ‘near miss’ events. In their series, a formal ‘time out’ was unsuccessful in preventing wrong-site surgery in 31 cases.12

Table I. Serious surgical events, as defined by the National Quality Forum (NQF).

| Surgical ‘never-events’ | |

|---|---|

| 1 | Surgery performed on the wrong body part. |

| 2 | Surgery performed on the wrong patient. |

| 3 | Wrong surgical procedure performed on a patient. |

| 4 | Unintended retention of a foreign object in a patient after surgery or other procedure. |

| 5 | Intra-operative or immediate post-operative death in an ASA class I patient. |

Jhawar, Mitsis and Duggal22 performed a national survey to estimate the incidence of wrong-side and wrong-level craniocerebral and spinal surgery among practising neurosurgeons in the Unites States.22 Among the 138 responding neurosurgeons, 25% admitted to having performed incisions on the wrong side of the head at one point during their careers. In addition, 35% of all neurosurgeons who had been in practice for more than five years disclosed a wrong-level lumbar spine procedure at some point.22 A review of the National Practitioner Data Bank and closed claims studies revealed that wrong-site surgery continues to occur approximately 1300 to 2700 times a year in the United States.23 By their very nature, there are intrinsic shortcomings to most studies designed to determine the incidence and frequency of wrong-site and wrong-patient procedures. There is a consistent risk of a selection bias related to the restricted selection to malpractice claims, which may just represent the ‘tip of the iceberg’ of all adverse events and surgical complications. To overcome this limitation, a study from our own group analysed a prospective physician insurance database of 24 975 physician self-reported adverse events.10 A total of 25 wrong-patient and 107 wrong-site procedures were identified during a six-and-a-half-year study period before and after implementation of the UP.10

In this study, the main root causes leading to wrong-patient surgery were errors in diagnosis (56%) and errors in communication (100%), whereas wrong-site occurrences were related to errors in judgment (85%) and the lack of performing a surgical ‘time out’ (72%). Nonsurgical specialties were found to be involved in the aetiology of wrong-patient procedures and to contribute equally with surgical disciplines to adverse outcome related to wrong-site adverse events. These data emphasise that surgical ‘never-events’ keep occurring despite implementation of the UP, and that the widespread mandatory use of a strict protocol-driven approach does not keep patients safe.5,10

Limitations of the protocol

On careful analysis, the pitfalls and limitations which may render the UP vulnerable to a breach in efficiency and compliance are hidden in each component of the protocol.5 Arguably, the degradation of the UP to a pure ‘robotic’ ritual leads to a distraction from the surgeon’s focus on the initial intent to provide safe surgical care to our patients. Furthermore, the inappropriate or inaccurate marking of the correct surgical site represents another major root cause of wrong-site surgery. Finally, the continuing expansion of the ‘time out’ to include secondary safety issues, such as antibiotic and venous thromboembolism prophylaxis (so-called ‘expanded’ time out),15,24 further dilutes the mission of the UP in its core essence, and likely contributes to decreased compliance and credibility of the protocol related to the ‘buy-in’ by the surgical team.5

Further levels of complexity which are likely to represent another underestimated risk factor for wrong-site surgery are added when multiple simultaneous procedures are performed in the same patient, which dilute the focus of the ‘time out’ on a single procedure. Another significant loophole in the system is the lack of a global implementation of the UP. This notion is supported by the demonstration that non-surgical specialties, such as internal and family medicine, are predominantly involved in the aetiology of wrong-patient surgery and contribute significantly to patient harm after wrong-site procedures.10 Based on these insights, we advocate a strict adherence to the UP also for non-procedural medical specialties that perform selected invasive procedures, such as chest tube insertions.

Concept of a pre-procedure verification process

Strikingly, about one third of all wrong-site and wrong-patient procedures originate before the patient’s admission to the hospital. Potential root causes include inaccurate clinic note dictations related to the surgical site, mislabelling of radiographs and other diagnostic tests, or a mix-up of patient identities with similar (or identical) names, and mistakes in theatre scheduling.10

The rationale for conducting a pre-procedure verification process is to confirm patient identity, the scope of the planned procedure, and the surgical site. Each patient is unequivocally identified by an identification bracelet which includes at least the patient’s name, birth date, and medical record number. The surgical consent form is presented to the patient, including the intended surgical procedure and the name of the responsible surgeon. The patient signs the consent form only after all pertinent information has been confirmed. Surgical site marking is performed by the surgeon, during or after the pre-procedure verification process. Finally, the team’s understanding of the planned procedure is confirmed to be consistent with the patient’s expectations. A checklist is used to review and verify that all documents and pertinent information are available, accurate, and completed, prior to moving the patient to the operating room.

Pitfalls in surgical site marking

Inadequate or inaccurate surgical site marking (i.e. marking of the wrong side/site, imprecise marking of the correct site, and inadequate modality of site marking) represents an important underlying root cause contributing to the risk of wrong-site surgery (Table II).

Table II. Examples of ‘classic’ pitfalls related to site marking

| 1. | The relegation of site marking to a junior member of the surgical team (e.g. intern) or to any other provider who will not be personally involved in the surgical procedure. |

| 2. | Wrong modality of marking the correct site (e.g. using an ‘X’ which may be misunderstood as ‘not this side’). |

| 3. | Marking of the wrong site based on misleading pre-procedure documentation (e.g. erroneous clinic note dictation, faulty documentation in chart and consent form, and mislabelling of diagnostic studies, e.g. radiographs). |

| 4. | Imprecise site marking, such as marking the correct anatomic location without specifying the operative site (e.g. medial vs lateral incision), marking an extremity without specifying the exact location and marking the correct spinal level on skin, but addressing the wrong level after surgical dissection. |

| 5. | The use of non-permanent markers may lead to the faulty assumption that the absence of visualised site markings prior to skin incision may be acceptable, as the marks may have been washed off during the preparation process. |

| 6. | Obsolete marking of the contralateral side (e.g. ‘no’ or ‘not this side’) will create confusion and uncertainty, particularly if marks are illegible or partially washed off (Fig 1). |

| 7. | Residual marks from a previous surgery in the same patient may distract from the correct surgical site during a follow-up intervention (e.g. in multiply injured patients with staged procedures at different time-points). |

| 8. | Inability or contraindication to mark the surgical site. |

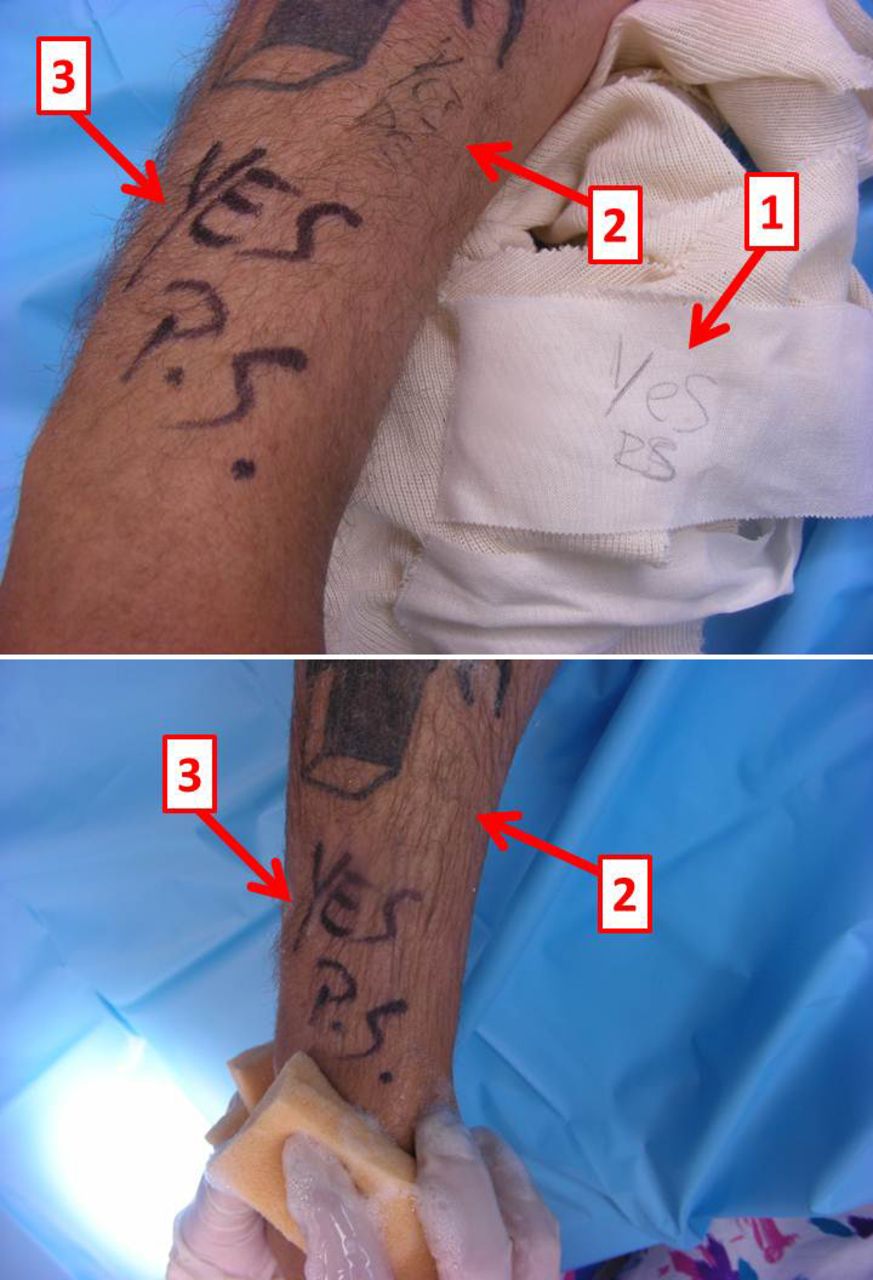

Fig. 1

Anecdotal photograph of an incorrect surgical site marking modality prior to a scheduled mastectomy on the contralateral side.

A number of specific circumstances may impede the adequate surgical site marking for technical or anatomic reasons. For example, site marking is impracticable on mucosal surfaces or teeth. Site marking is furthermore considered contraindicated in premature infants, due to the risk of introducing a permanent skin tattoo. Some surgical sites are inaccessible for accurate external marking, including in visceral surgery (internal organs), neurosurgery (brain, spine), interventional radiology (vascular procedures), and orthopaedic surgery on the torso (pelvis, spine). Rarely, patients may refuse surgical site marking for cosmetic reasons or other personal preferences.

To overcome these limitations and potential pitfalls, a defined alternative process must be in place. Radiological diagnostics must be consulted pre- and intra-operatively to determine the correct surgical site with accuracy. For example, spinal surgeons must ensure the correct intervertebral level using intra-operative fluoroscopy in conjunction with meticulous scrutiny in assessing pre-operative radiographs (CT scans, MRI) in order to avoid a wrong-level spine fusion, particularly in the presence of unusual spinal anatomy.21,22 General surgeons have to rely on pre-operative imaging and/or ‘on-table’ cholangiogram to ensure clipping the correct bile duct during a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. In a similar situation, interventional radiology providers are at risk of erroneous coiling of the wrong artery. Finally, neurosurgical interventions on the wrong part of the brain keep being reported in regular intervals.18,22,25

Unlike symmetric external body parts (extremities, eyes, ears), any ‘hidden’ surgical site is not easily identified, confirmed and marked prior to surgery. Thus, such particular circumstances mandate the scrutiny of intra-operative surgical site localisation under fluoroscopy, in conjunction with a careful evaluation of available pre-operative diagnostic tests, such as CT, MR, angiography, or cholangiography (Table III).

Table III. Surgical site marking: tips and tricks

| 1 | Site marking must be performed by a licensed practitioner who is a member of the surgical team and will be present during the surgical ‘time out’ and the procedure. Ideally, this should be done by the lead surgeon in charge. |

| 2 | Site marking must occur at the latest in the pre-operative holding area, before moving the patient to the operating room or to any other procedural location. |

| 3 | Patients should be involved in the site marking process whenever possible. |

| 4 | Site marking must be unambiguous, using clearly defined terminology such as ‘YES’, ‘GO’, ‘CORRECT’, or ‘CORRECT SITE’. The exact marking modality must be standardised and consistent within a specific institution. |

| 5 | Responsibility of site marking should be confirmed by adding the surgeon’s initials. The exception is a surgeon’s name with the initials ‘N.O.’, which can be confounded with ‘no’, implying that the marked site should not be operated on. |

| 6 | Site marking must be applied by indelible ink on skin, using permanent markers. The use of temporary or removable markers (e.g. using stickers or marking on casts or dressings), is not feasible (Fig 2). |

| 7 | Site marking must be resistant to the surgical preparation process and remain visible at the time of skin incision. |

| 8 | Sterility of the marking ink or marking pen is not required, and the use of non-sterile markers has been shown not to increase the risk of post-operative infections.26-29 |

| 9 | Site marking must be applied near or at the incision site. The side, level, and location of the procedure must be unequivocally defined by the marking, whenever possible. |

| 10 | Site marking takes into consideration the side (laterality), surface (flexor/extensor, medial/lateral), the spinal level, and the specific digit or lesion on which to be operated. |

| 11 | Increased awareness in all cases where precise site marking is not possible (see ‘pitfalls’ above). |

| 12 | Knowledge of contraindications for surgical site marking, including premature infants (risk of permanent tattoo), mucosal surfaces, teeth, and patients refusing a surgical site marking for personal reasons. |

| 13 | Implementation of defined alternative processes for any circumstance where surgical site marking is not feasible. |

Fig. 2

Photographs showing the ‘dos and don’ts’ of technical options for surgical site marking.Top image: this patient was scheduled for a surgical procedure on the right forearm. 1) The intern marked and initialed the site on the dressing, which came off prior to surgery. 2) The resident corrected the mistake by marking the surgical site on skin, using a regular pen. Neither the marking nor the initials is legible. 3) The site was again marked and initialed by the attending surgeon with a permanent marker. Bottom image: during the surgical preparation, the site marking with a regular pen 2) was washed off immediately, whereas the permanent marker 3) remained visible throughout the surgical preparation. This example emphasises the crucial importance of using a permanent marker, large and legible letters, and to sign the marking with the surgeon’s initials. “YES” is the designated, standardised identifier for the correct surgical site at Denver Health Medical Center.

Critical aspects of the surgical ‘time out’

The last part of the UP, the surgical ‘time out’, is performed in the operating room, before the procedure is initiated. The ‘time out’ represents the final reassurance of accurate patient identity, surgical site, and planned procedure. In addition, the correct patient positioning, the need for peri-operative antibiotics, presence of allergies, and the availability of relevant documents and diagnostic tests, instruments, implants and other pertinent equipment are confirmed during this time. Table IV lists parameters that are key to success for a surgical ‘time out’:

Table IV. Key parameters for a successful ‘time out’.

| 1. | A ‘time out’ is called by any member of the surgical team, typically by a specifically designated person who is not directly involved in the procedure (e.g. the circulating nurse). |

| 2. | In a two-tiered ‘time out’, the patient is awake and participating in the verification process (so-called ‘awake time out’), followed by a repeat ‘time out’ immediately before skin incision, with the intent of avoiding prepping and draping of the wrong surgical site after the ‘awake time out’. |

| 3. | The ‘time out’ process must be standardised in every institution. |

| 4. | All immediate members of the procedural team (surgeon, anaesthetist, circulating nurse, operating room technician, etc.) must actively participate in the ‘time out’ and introduce themselves by name and role. |

| 5. | All routine activities are suspended during the ‘time out’ to an extent which does not compromise patient safety. |

| 6. | The ‘time out’ must be repeated intra-operatively for every additional secondary procedure performed on the same patient. |

Conclusion

Despite widespread implementation of the UP in the United States, this standardised protocol has failed to prevent severe complications and ‘never-events’ from occurring.10,16,17,21 This article addresses potential technical pitfalls and selected loopholes and vulnerabilities in the system. All healthcare institutions (not just in the United States) across all specialties (not just surgical disciplines) should commit to adherence to the UP or an alternative standardised process, such as the WHO checklist, as a reliable quality assurance tool. Individual practitioners’ preferences in site marking modalities must be avoided by introducing a standard system across institutions.30 Patients should be involved in the site marking process and encouraged to inquire of their surgeons whether a formal ‘time out’ procedure will occur in the surgical suite. Our long-term aim is directed towards educating ourselves, the next generation of healthcare providers, and our patients, to strive for a sustainable and unfailing patient safety culture. Beyond a doubt, this requires a physician-driven team approach. The ultimate determinant of success is the commitment and ‘buy-in’ by the entire surgical team.

1 Haynes AB , WeiserTG, BerryWR, et al.A surgical checklist to reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. N Engl J Med2009;360:491–499. Google Scholar

2 de Vries EN , DijkstraL, SmorenburgSM, MeijerRP, BoermeesterMA. The SURgical PAtient Safety System (SURPASS) checklist optimizes timing of antibiotic prophylaxis. Patient Saf Surg2010;4:6.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

3 Ram K , BoermeesterMA. Surgical safety. Br J Surg2013;100:1257–1259.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

4 Norton E . Implementing the universal protocol hospital-wide. AORN J2007; 85:1187–1197.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

5 Stahel PF. Lessons learned from wrong-site, wrong-patient surgery. http://www.physiciansweekly.com/lessons-learned-from-wrong-site-wrong-patient-surgery/ (date last accessed 7 January 2014). Google Scholar

6 Sparks EA , Wehbe-JanekH, JohnsonRL, SmytheWR, PapaconstantinouHT. Surgical safety checklist compliance: a job done poorly!. J Am Coll Surg2013;217:867–873.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

7 Hannam JA , GlassL, KwonJ, et al.A prospective, observational study of the effects of implementation strategy on compliance with a surgical safety checklist. BMJ Qual Saf2013;22:940–947.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

8 O'Connor P , ReddinC, O'SullivanM, O'DuffyF, KeoghI. Surgical checklists: the human factor. Patient Saf Surg2013;7:14.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

9 Clarke JR , JohnstonJ, BlancoM, MartindellDP. Wrong-site surgery: can we prevent it?Adv Surg2008;42:13–31.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

10 Stahel PF , SabelAL, VictoroffMS, et al.Wrong-site and wrong patient procedures in the era of the Universal Protocol – analysis of a prospective database of physician self-reported occurrences. Arch Surg2010;145:978–984. Google Scholar

11 No authors listed. Wrong site surgery and the Universal Protocol. Bull Am Coll Surg 2006;91:63. Google Scholar

12 Clarke JR , JohnstonJ, FinleyED. Getting surgery right. Ann Surg2007;246:395–403. Google Scholar

13 Dillon KA . Time out: an analysis. AORN J2008;88:437–442. Google Scholar

14 Edwards P . Ensuring correct site surgery. J Perioper Pract2008;18:168–171.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

15 Hunter JG . Extend the universal protocol, not just the surgical time out. J Am Coll Surg2007;205:4–5. Google Scholar

16 Lembitz A, Clarke TJ. Clarifying 'never events' and introducing 'always events'. Patient Saf Surg 2009;3:26. Google Scholar

17 Catalano K . Have you heard? The saga of wrong site surgery continues. Plast Surg Nurs2008;28:41–44.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

18 Shinde S , CarterJA. Wrong site neurosurgery: still a problem. Anaesthesia2009;64:1–2. Google Scholar

19 van Hille PT . Patient safety with particular reference to wrong site surgery: a presidential commentary. Br J Neurosurg2009;23:109–110. Google Scholar

20 Wong DA , HerndonJH, CanaleST, et al.Medical errors in orthopaedics: results of an AAOS member survey. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]2009;91-A:547–557. Google Scholar

21 Lindley EM, Botolin S, Burger EL, Patel VV. Unusual spine anatomy contributing to wrong level spine surgery: a case report and recommendations for decreasing the risk of preventable 'never events'. Patient Saf Surg 2011;5:33. Google Scholar

22 Jhawar BS , MitsisD, DuggalN. Wrong-sided and wrong-level neurosurgery: a national survey. J Neurosurg Spine2007;7:467–472.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

23 Seiden SC , BarachP. Wrong-side/wrong-site, wrong-procedure, and wrong-patient adverse events: are they preventable?Arch Surg2006;141:931–939.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

24 Altpeter T , LuckhardtK, LewisJN, HarkenAH, Polk HC Jr. Expanded surgical time out: a key to real-time data collection and quality improvement. J Am Coll Surg2007;204:527–532.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

25 Mitchell P , NicholsonCL, JenkinsA. Side errors in neurosurgery. Acta Neurochir (Wien)2006;148:1289–1292.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

26 Cronen G , RingusV, SigleG, RyuJ. Sterility of surgical site marking. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]2005;87-A:2193–2195.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

27 Cullan DB 2nd , WongworawatMD. Sterility of the surgical site marking between the ink and the epidermis. J Am Coll Surg2007;205:319–321.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

28 Rooney J , KhooOK, HiggsAR, SmallTJ, BellS. Surgical site marking does not affect sterility. ANZ J Surg2008;78:688–689.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

29 Zhao X , ChenJ, FangXQ, FanSW. Surgical site marking will not affect sterility of the surgical field. Med Hypotheses2009;73:319–320.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

30 Stahel PF , MehlerPS, ClarkeTJ, VarnellJ. The 5th anniversary of the “Universal Protocol“: pitfalls and pearls revisited. Patient Saf Surg2009;3:14. Google Scholar